Recently, I found two strange defects in my workshop, noteworthy to write it down.

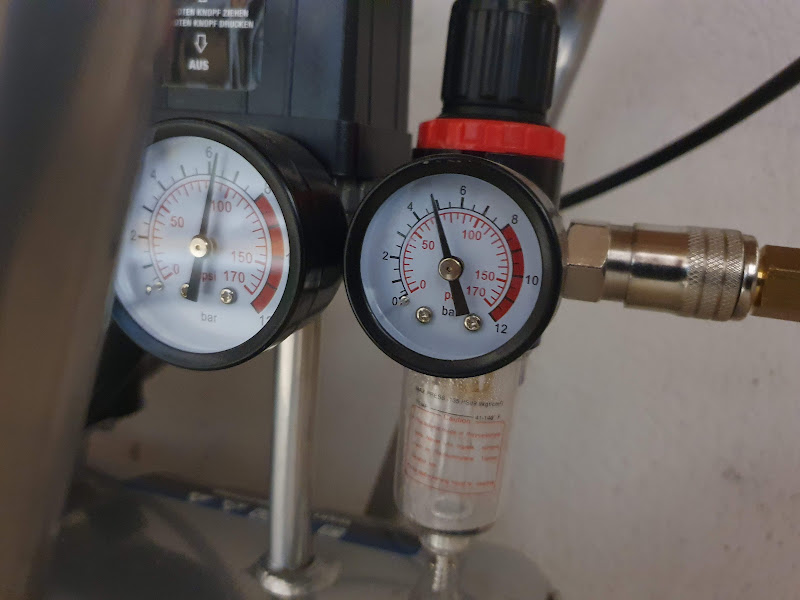

Ever since I expanded my workshop I notices some losses of compressed air, i.e., when coming back after a business trip, the pressure of the compressed air pipework is down from normally 6.5 bars, to only 2-3 bars, or even less after a longer vacation. I had attributed it to some leaking air gun or something like that, but finally I did a search and found various leaks at one distribution point.

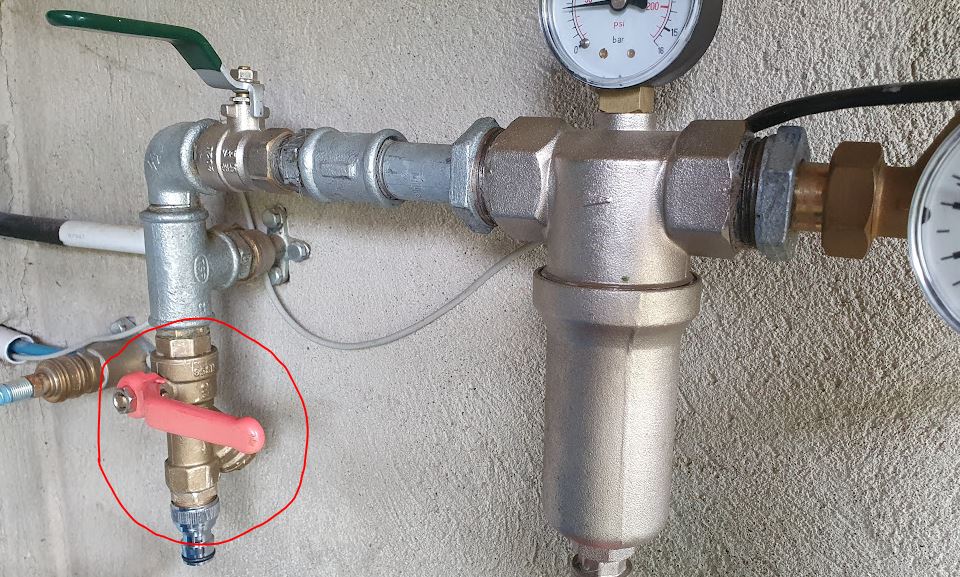

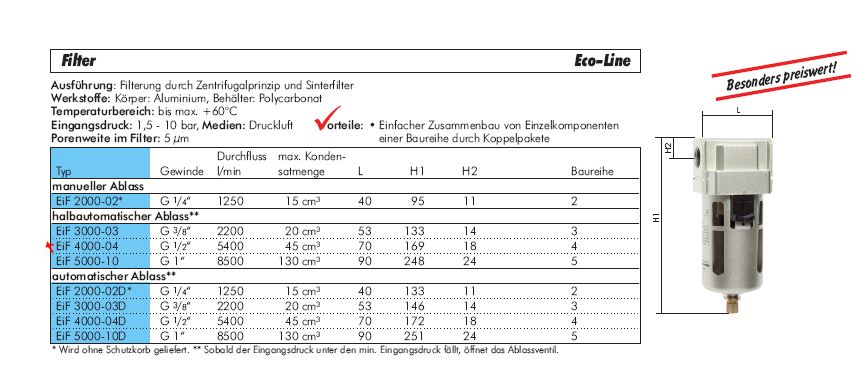

(1) the water mist filter had a leak at the drain valve — fixed it by closing it altogether. There is not too much water collected, it is installed only to avoid dust and such getting into the system further downstream.

(2) one of the fitting was leaking, because strangely there are some air fittings available that neither have a seal surface, nor conical thread, to it is hard to get it tight by tread tape in the first place (sometime I resorted to gluing-in those fittings with Epoxy glue).

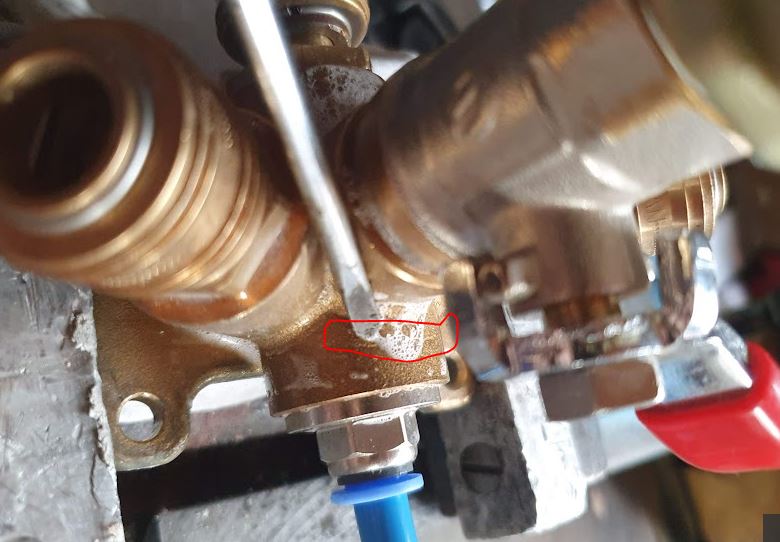

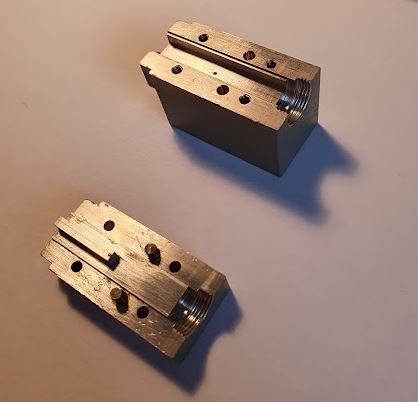

(3) Still, when checking with some soapy water – bubbles at the distribution fitting (5 connections 1/2″). Strange, strange, strange.

Clearly, a defective casting with a hairline crack leak. Maybe the temperatures or the mold or the liquid brass were not right, or the pouring wasn’t steady enough.

The defect line goes all around the fitting, otherwise I would have tried to file it out and solder it tight. Anyway, it is not worthwhile to fix such part at the risk of it failing again. So I replaced it with a new fitting at the cost of EUR 9.90 and at least 3 hours of work to get it all investigated, replaced, fitted and leak tested. Maybe a good idea to fully upgrade the pressurized air system of my workshop, which is now a combination of various distribution pieces, hoses, connectors. But there are trade-offs of perfection, cost, and efficiency — I have actually installed some air pressure distribution pipes for others (like, polyamide pipe, PE-Al composite pipe), but at my own workshop, I will be dealing with a less perfect system, at least, the major leaks have now been found and eliminated.

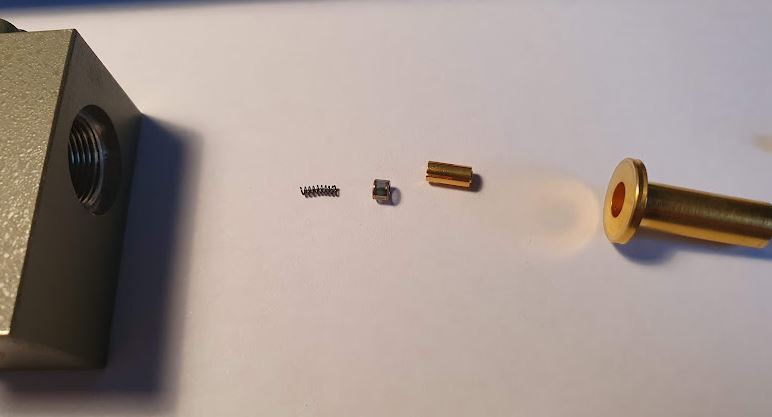

Another instance of strange failures, I noticed some problems with a bench vice, the smaller size vice I use regularly, and have been using since my childhood. If I remember right, I bought it for something like 35 Deutschmarks way back around ~1990. After all these years, it had some failures, the spindle pin sheared off once (maybe because I tightened it too much), and also a retaining piece of the front part of the spindle wore out (probably very soft steel and insufficient lubrication). Also some part of the casting broke off before, circled in black. Now, I almost injured myself as a part came loose unexpectedly, finally, as they say, always check the tool before you use it.

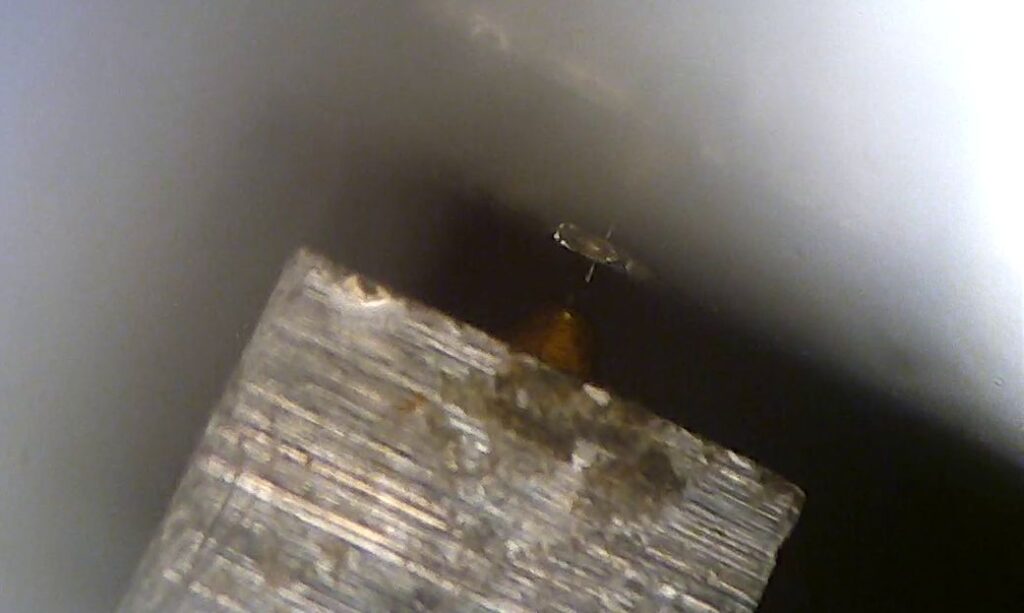

Didn’t need to go far, a major crack of the dovetail guideway.

It is cracked through, but holding on enough so that the defect is not easily seen without disassembly.

Finally, a cast iron bench vice, after 33 years of service (not always careful use), it may eventually break.

For replacement, I wanted a slightly bigger bench vice, 115 mm width. Also, a solid steel vice that is not too bulky and has a strong grip. These don’t come cheap, but I found a good (but rusty) Peddinghaus Matador steel vice for 35 EUR used, listed in online adds.

After some cleaning, adjustment, and other TLC, it is installed on the bench and working great. Definitely a step up.