With the repair of many spectrum analyzers, it turns out, the preselectors are usually not easily damaged, because of their self limiting characteristics, and because of the absence of active parts. The SYTF is diffient in that it has an active part, a switch.

It is already some years old, but no reason why such parts should have much aging at all.

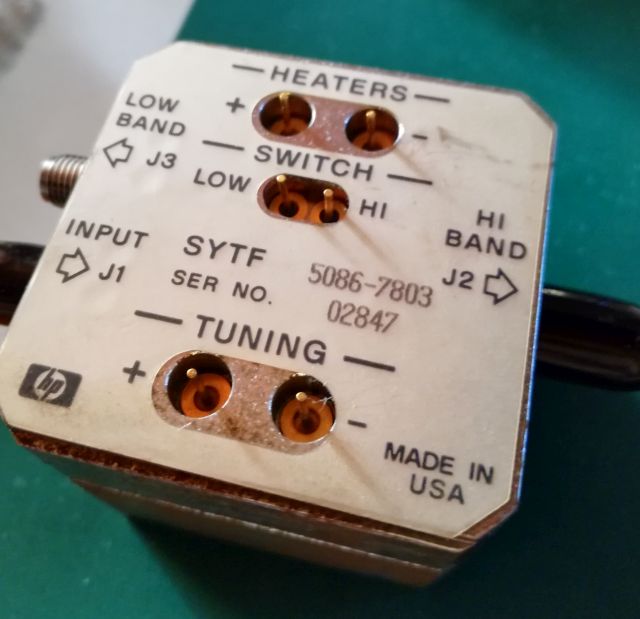

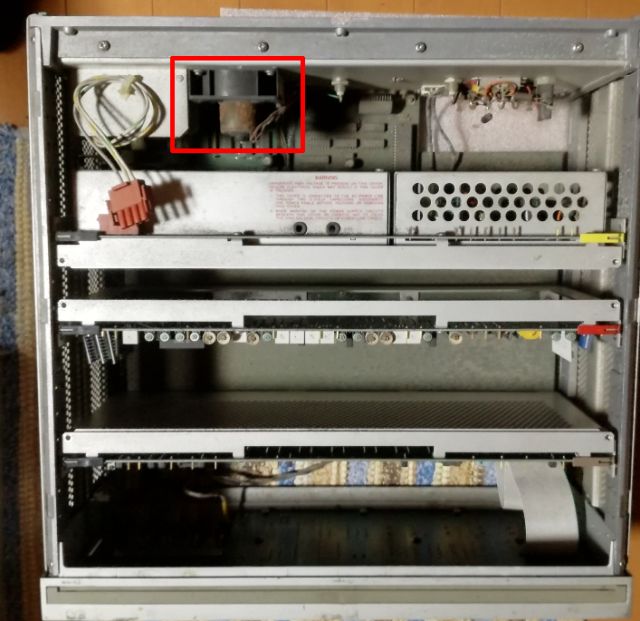

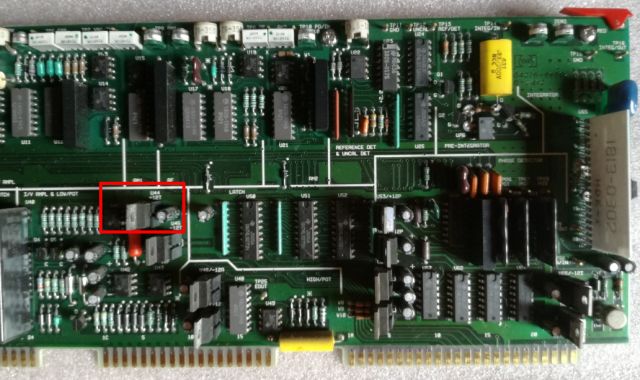

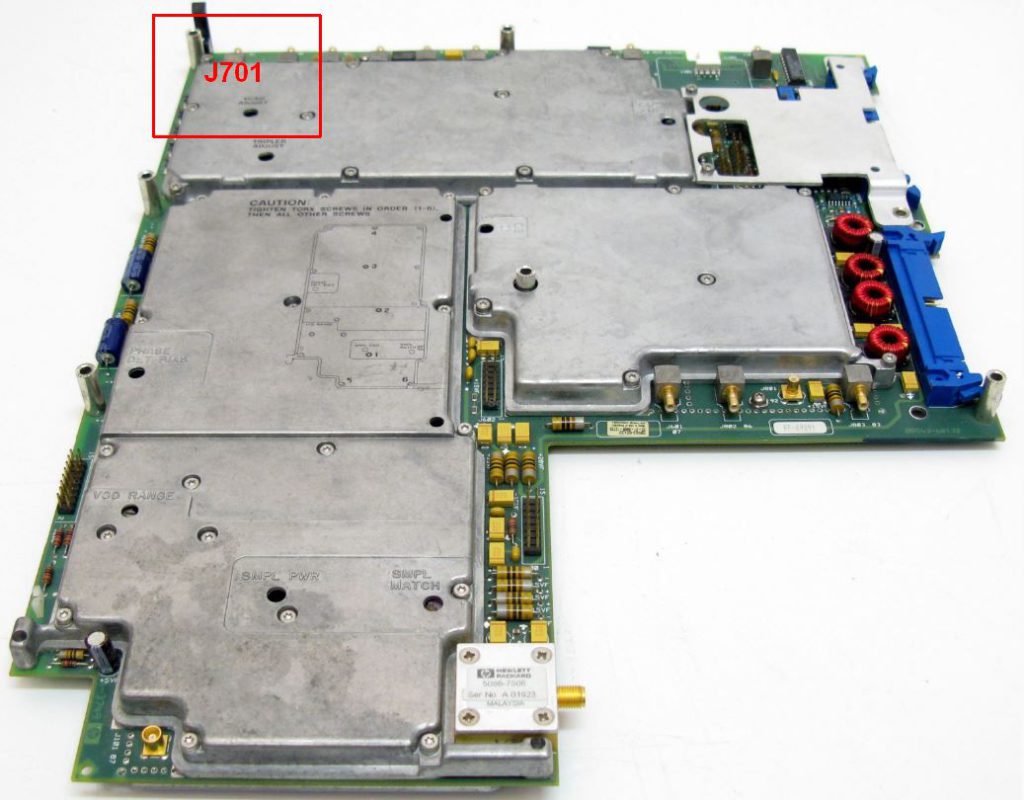

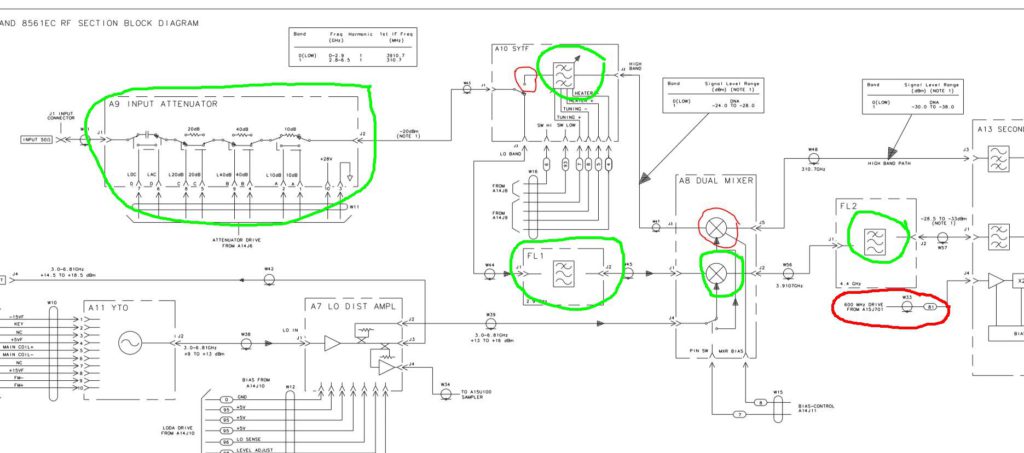

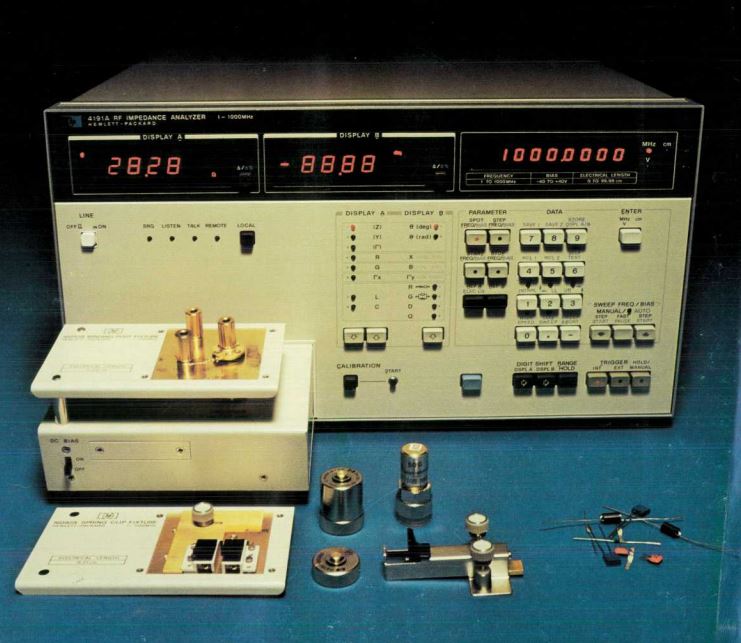

The symptom of this unit, it is working in the low frequency region setting, LOW band out, but the high band is dead, loss in excess of 35 dB, at all frequencies, and independent of the tuning current supplied.

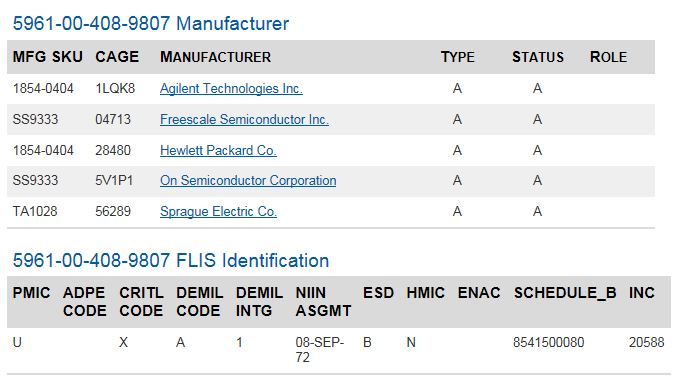

So my first assessment was, this unit needs replacing, and I found a replacement part online, from a US seller, not cheap, but OK, the 8561E analyzer is worth it, if it is working again after the repair. Unfortunately, several week of waiting were all for nothing – the seller shipped the wrong part and it took a while to get the money back, but finally all settled, except, we still have the defective filter.

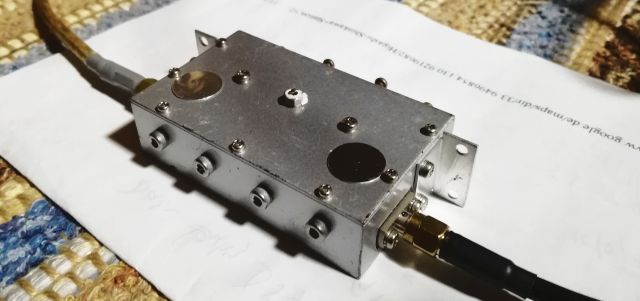

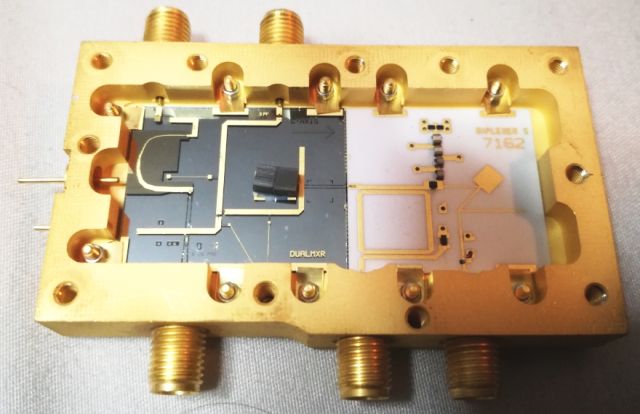

Let’s try to investigate the nature of the defect, and open it up. Fortunately, these filters are not hermetically welded like some other YIG parts.

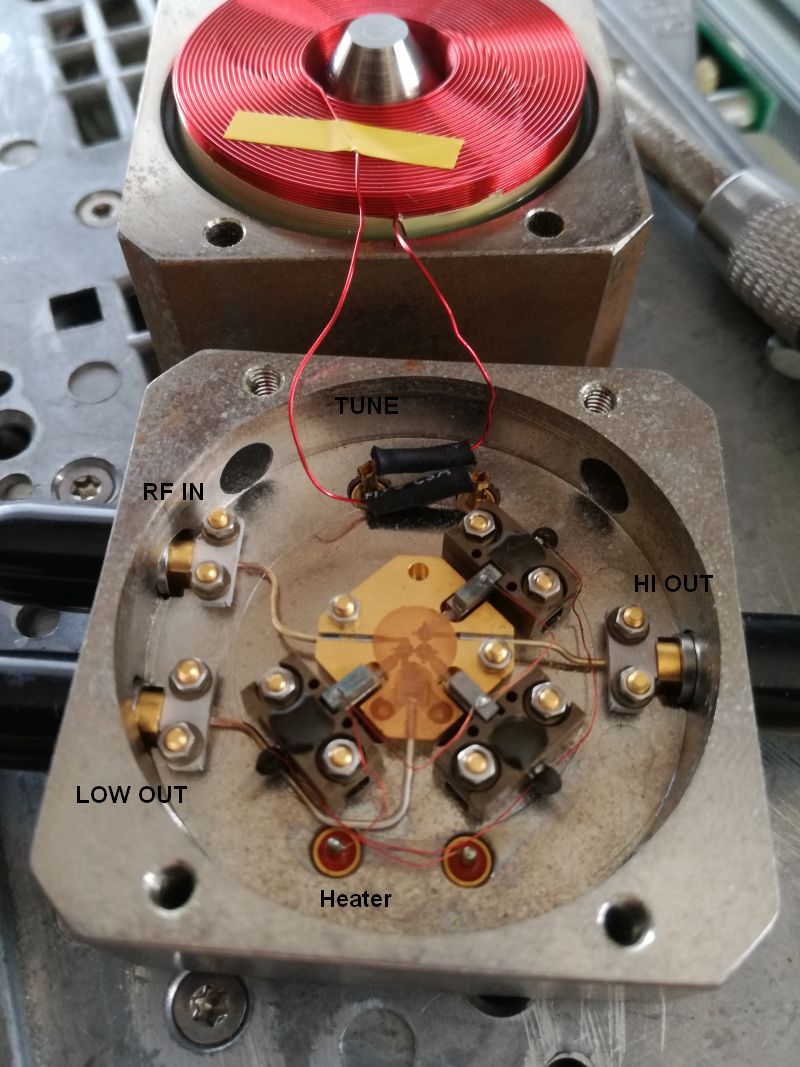

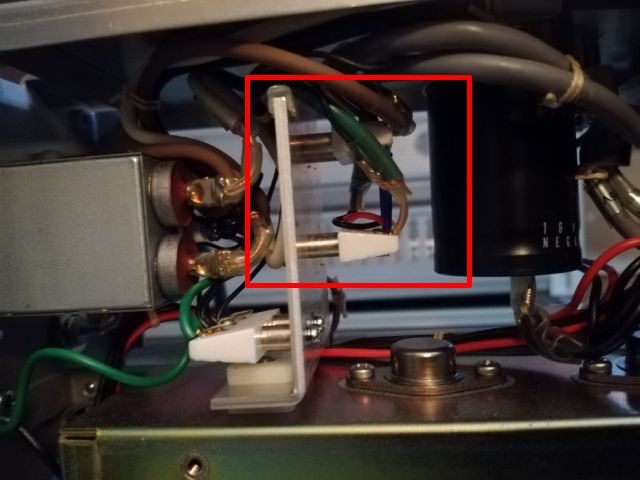

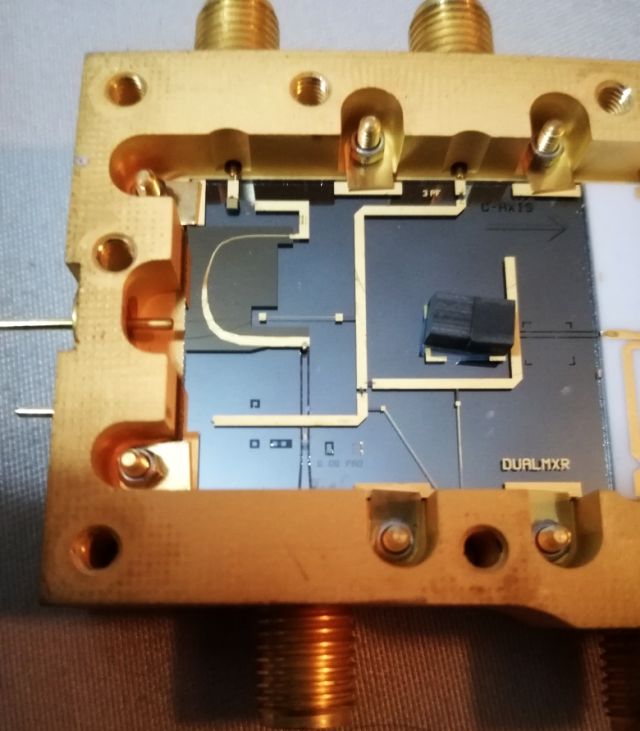

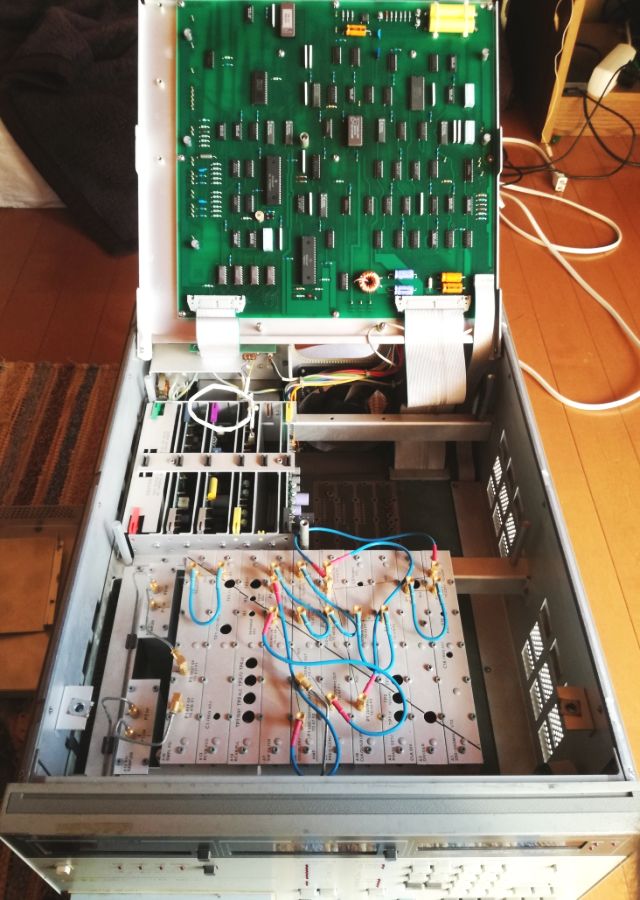

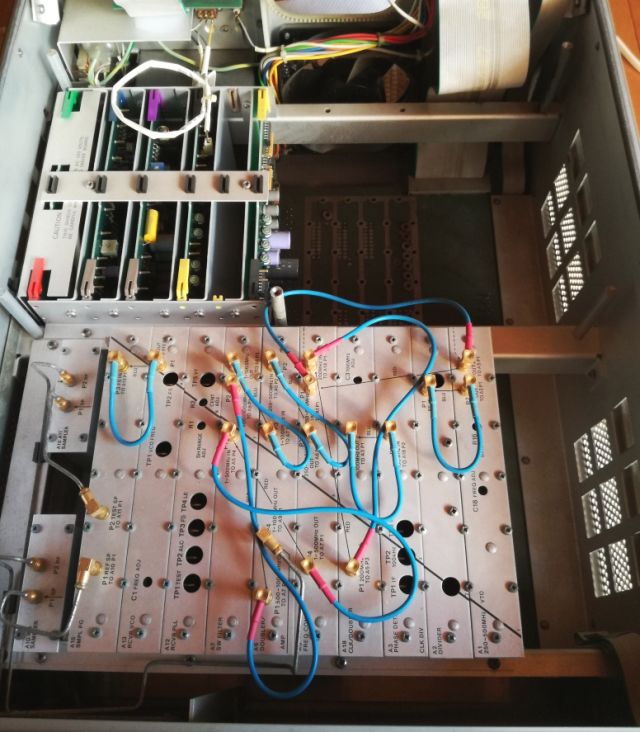

You can clearly see the coil, the inlet and outlets (low and high band) by rigid SMA cable (1 mm size!).

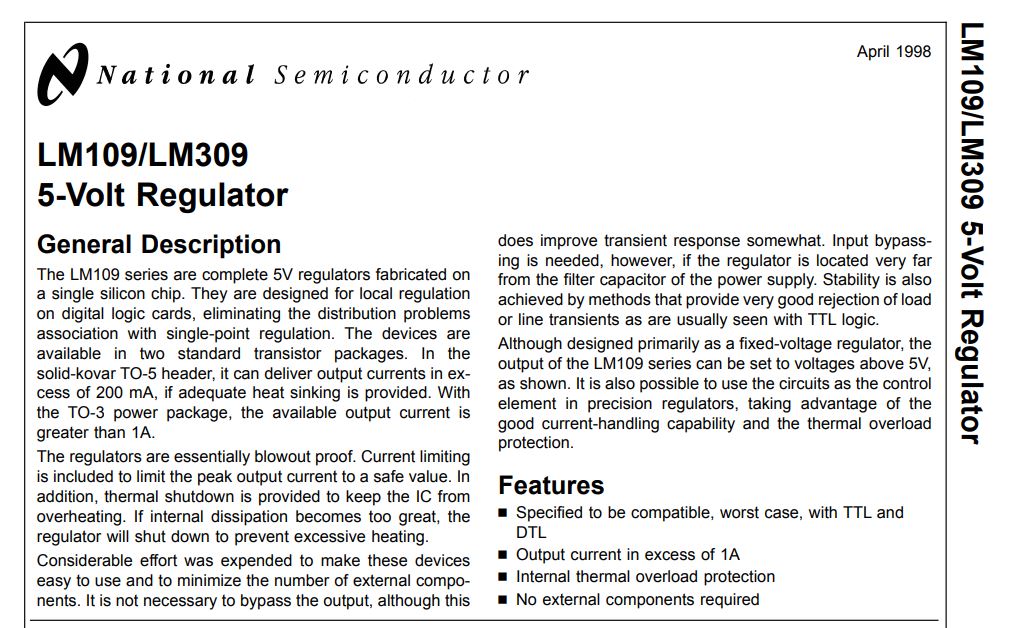

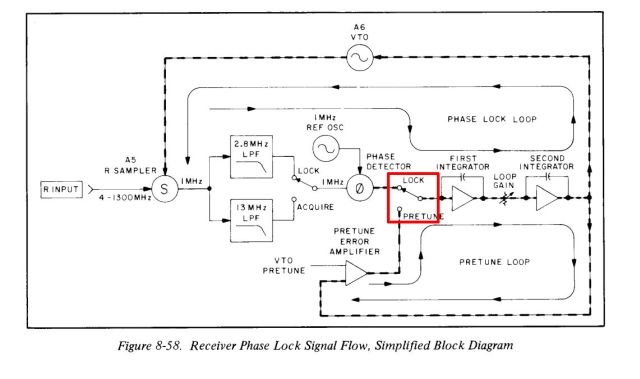

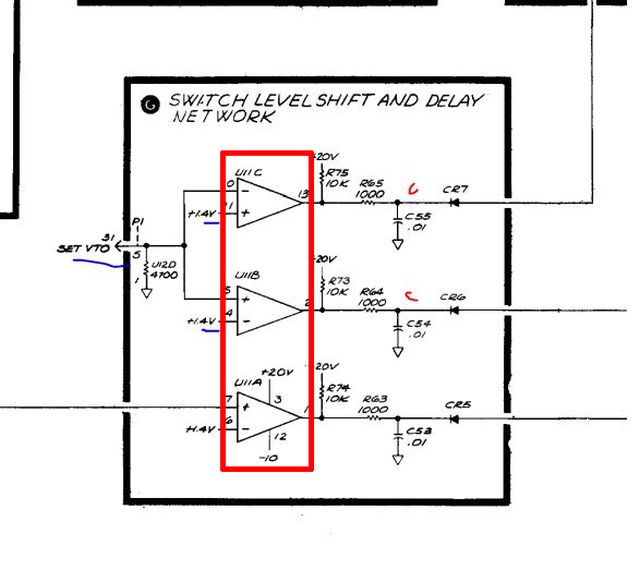

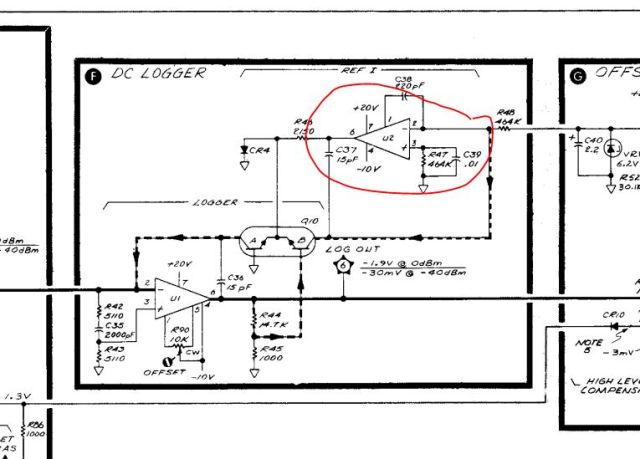

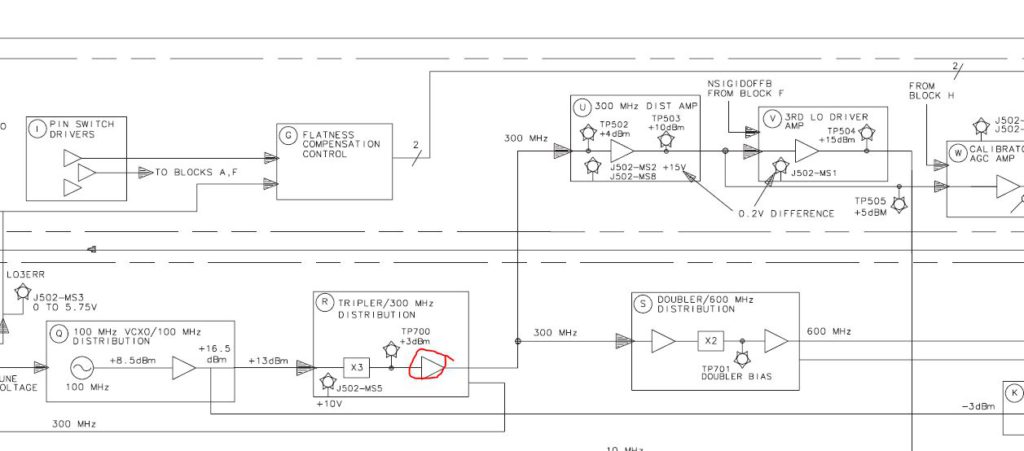

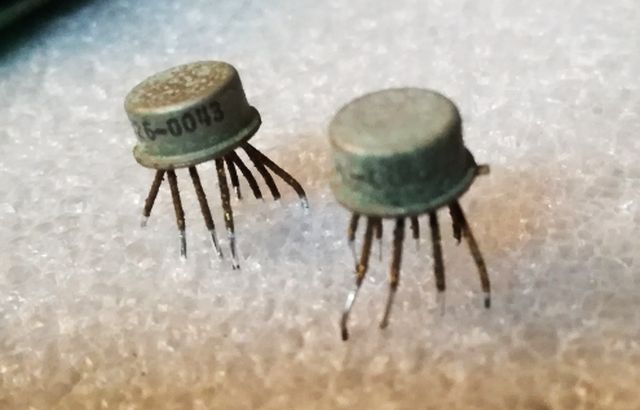

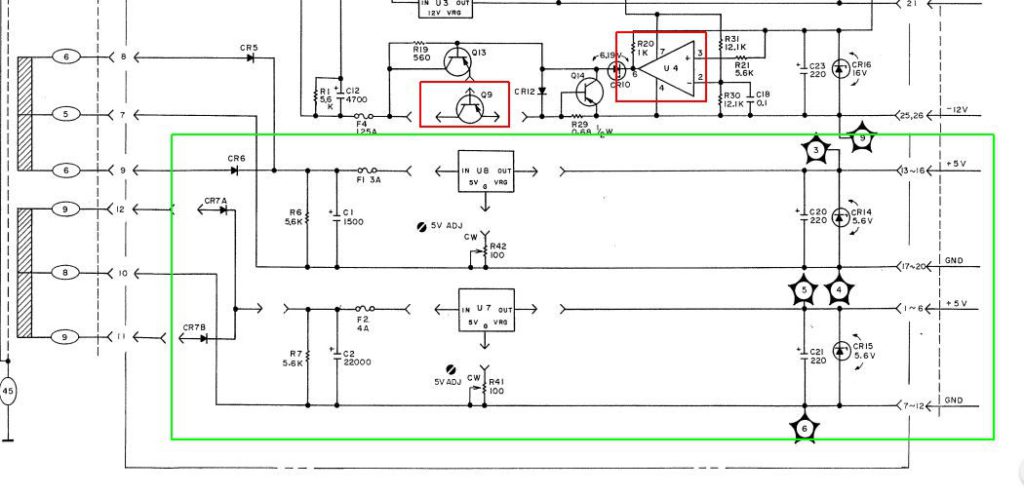

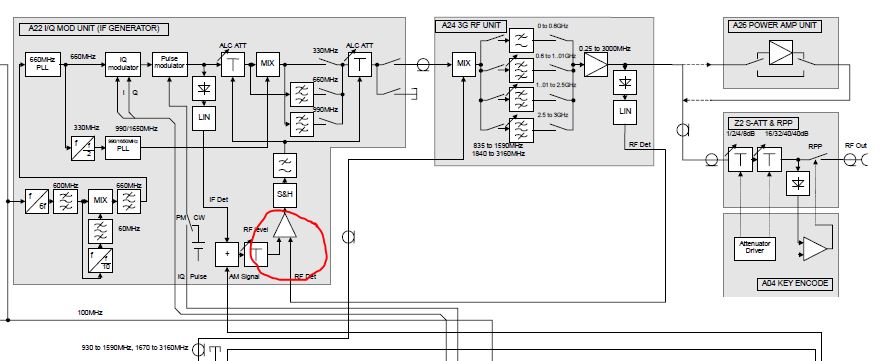

First, let’s study the switch. It is not actually switching the high band, as I originally assumed, but it is switching on and off the low band.

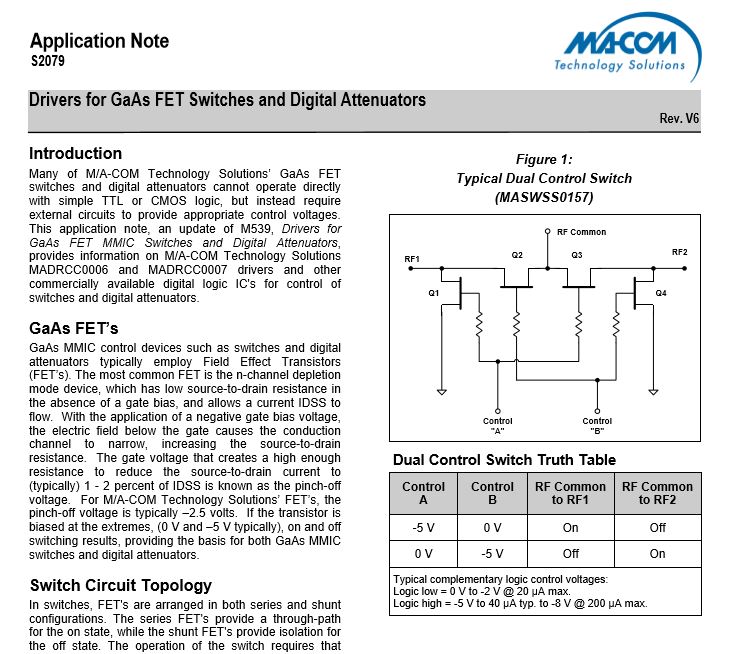

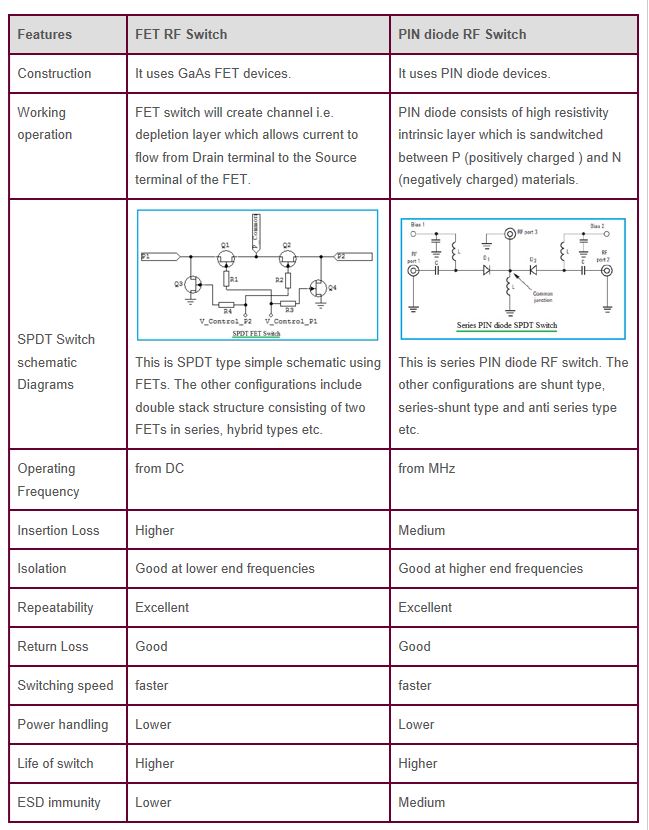

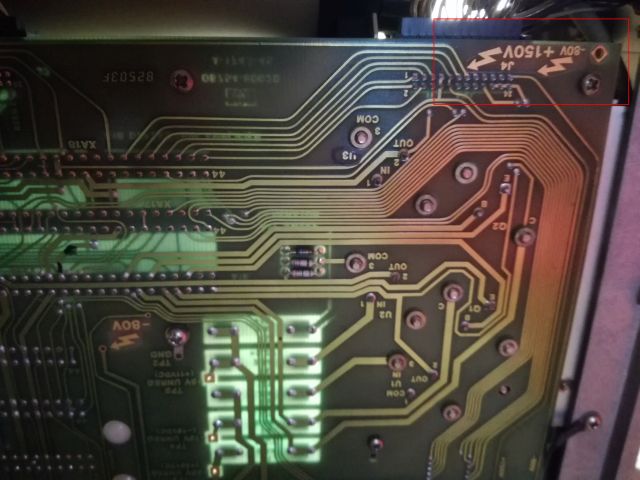

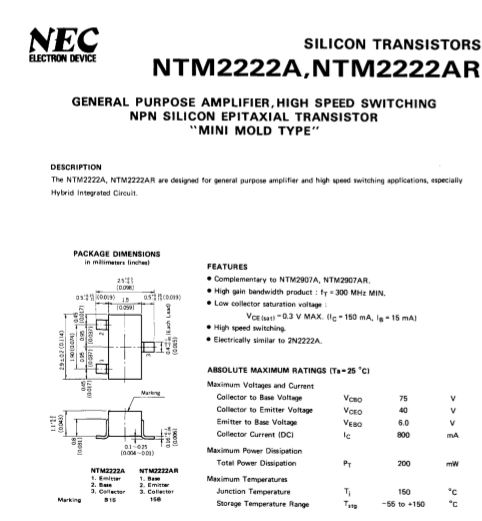

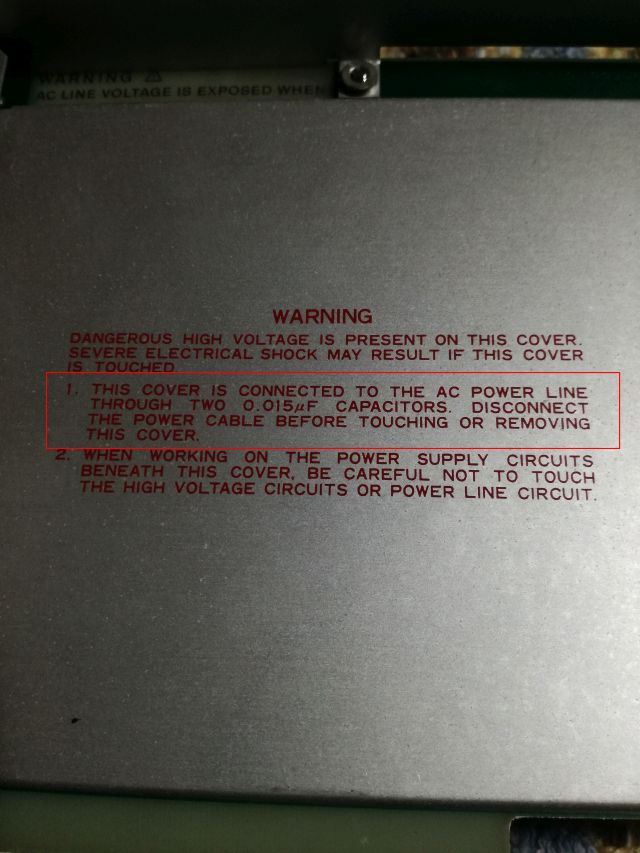

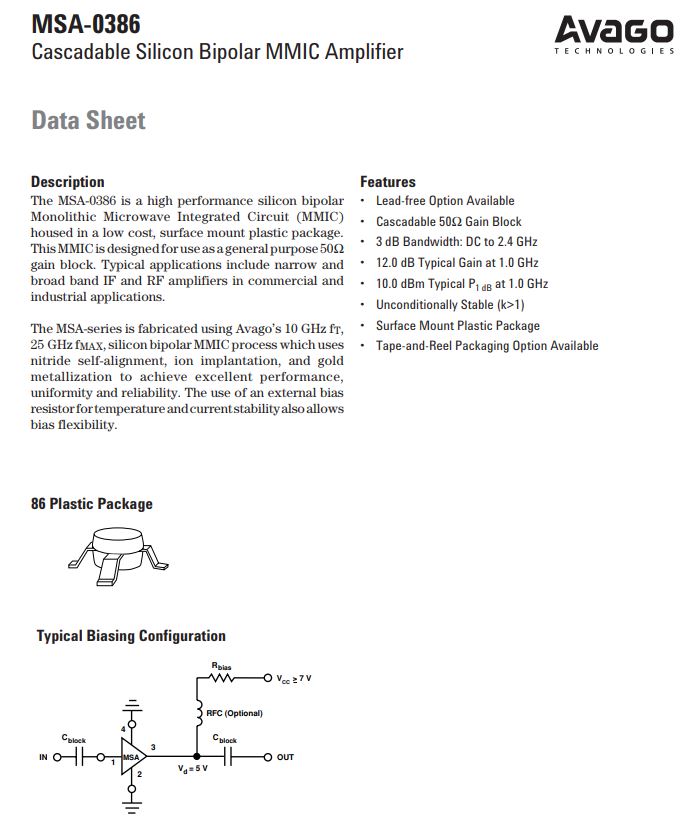

It is a series-shunt-series type FET switch, controlled by about -10 V negative voltage (1 kOHM vs. -15 V connection is the usual control method, floating or ground to switch off).

I could not find the exact die and model for this switch, but there are many similar models that clearly show the structure. The shunt and double series construction will provide very high isolation.

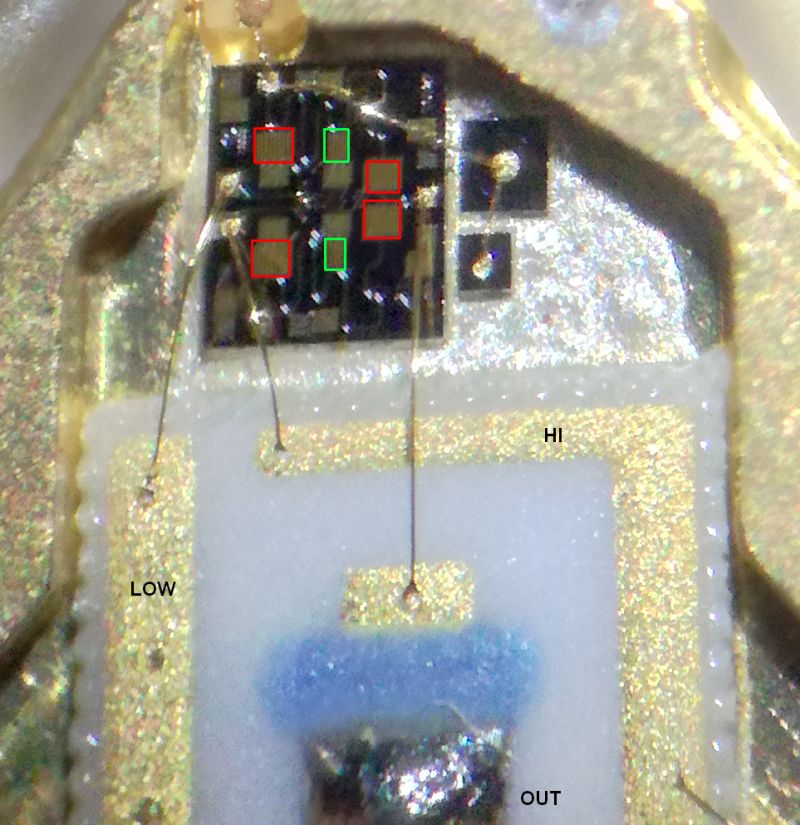

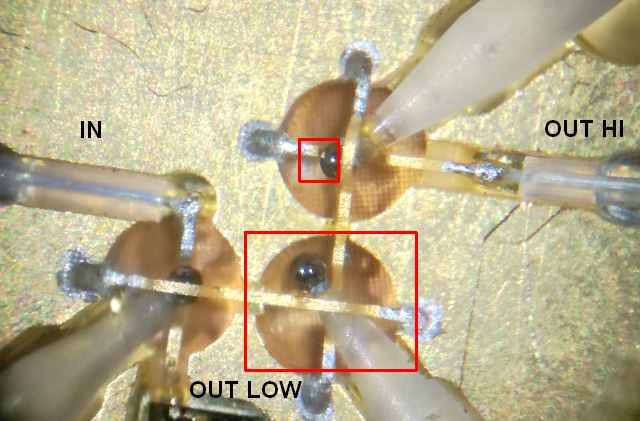

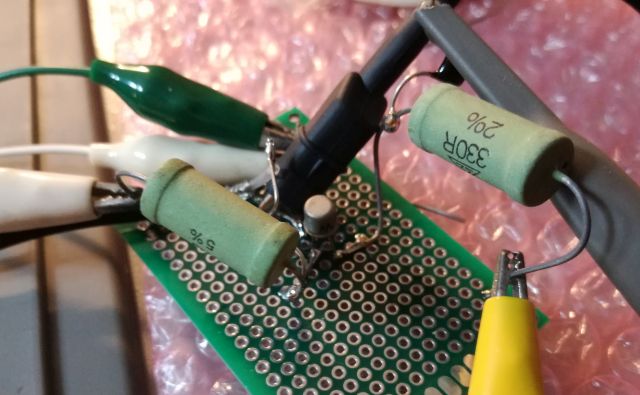

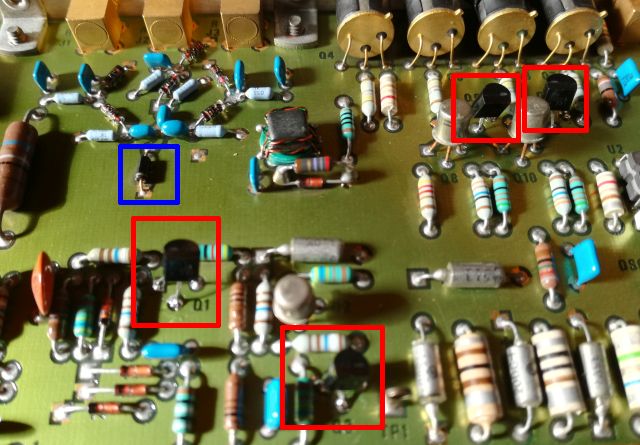

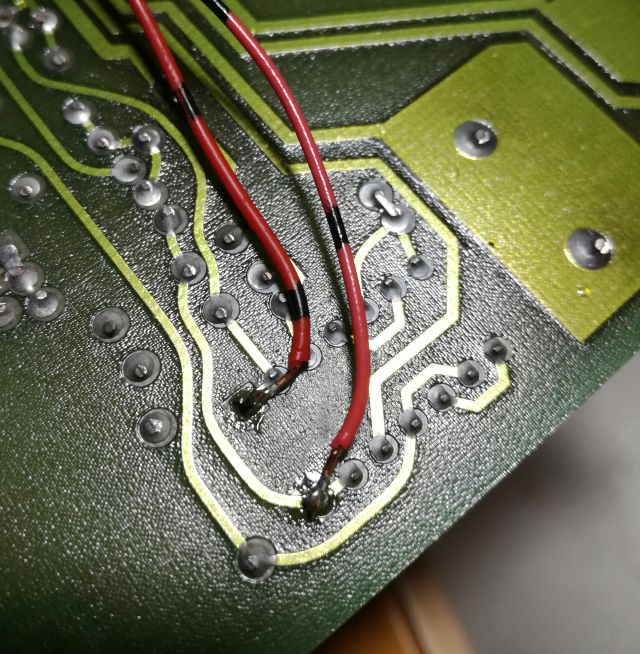

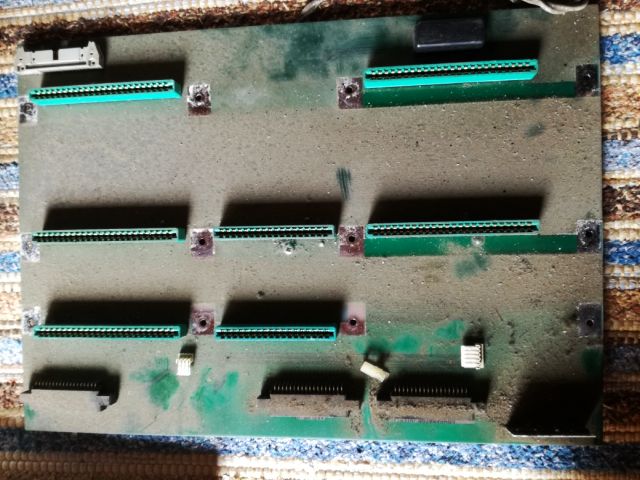

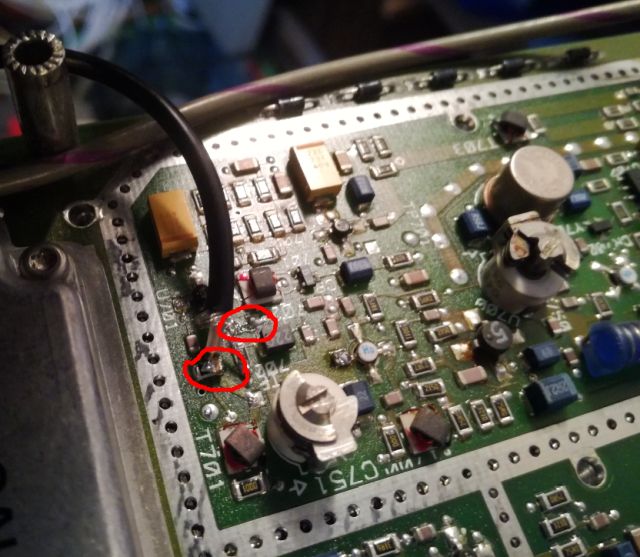

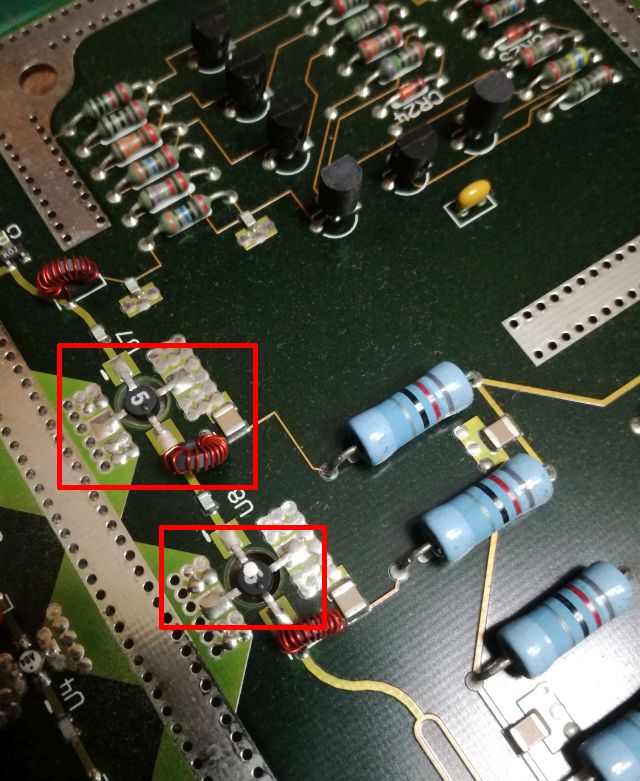

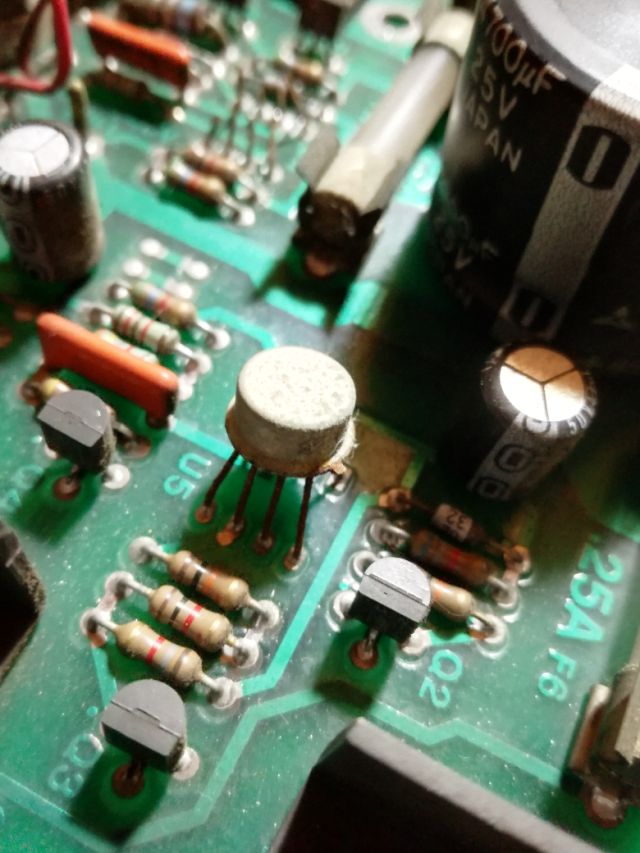

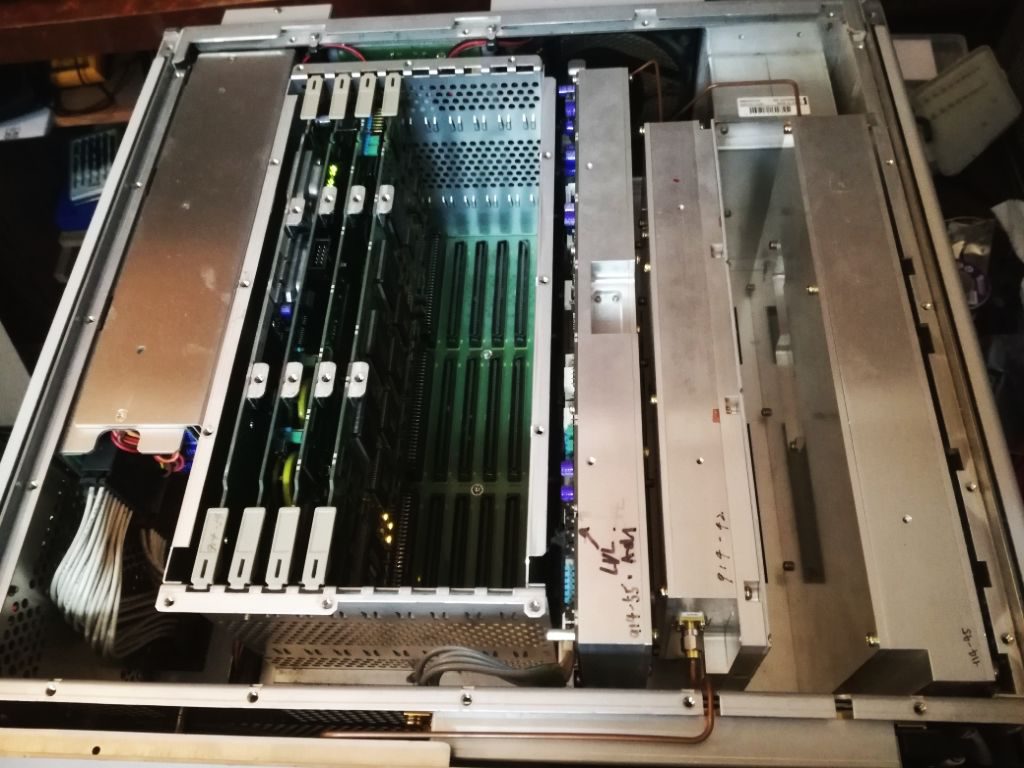

After removing carefully the gold mesh (it is only lightly glued on, I will use some tiny traces of epoxy to stick it back on), some study under the microscope.

Clearly, the spheres are misaligned! The spheres must be placed in the center of the coupling loop, to allow for RF to couple. Generally speaking, during alignment, the sphere is only turned, and then the position fixed by some epoxy – which all seems to be intact, and solidly fixed. So what has happended? I think it has to do with the mounting blocks, which are of different material compared to the based (which needs to be magnetic Fe-Nickel alloy). With frequent temperature cycling, I believe there is some migration of the mounting blocks, fractions of a micrometer every time (keep in mind, the YIG spheres are heated during operation). While we can speculate about the reason of the migration, the result is clear, and the action as well: we need to realign the spheres.

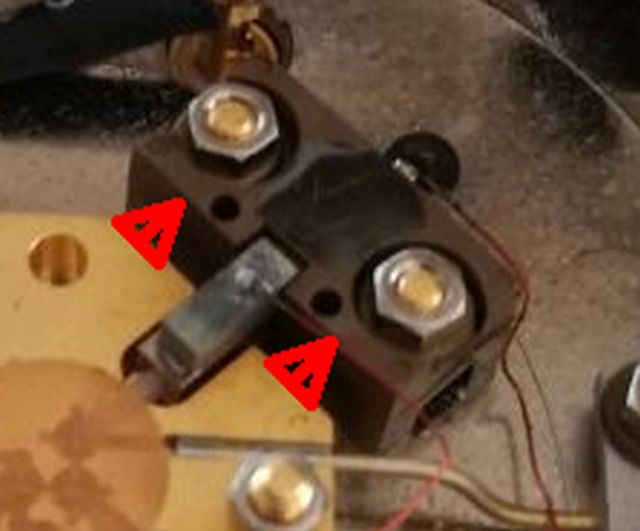

I decided not to undo the screws because the coupling loops can be easily damaged, and used a screwdriver to carefully push the mounting blocks away from the coupling section, bit by bit, under control with a microscope.

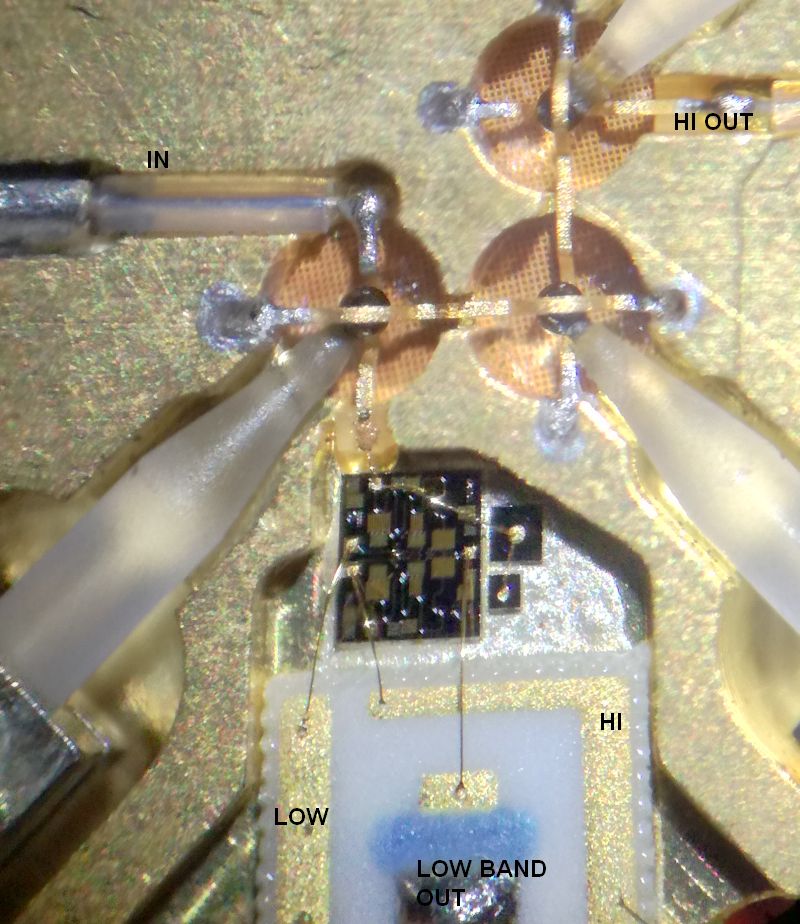

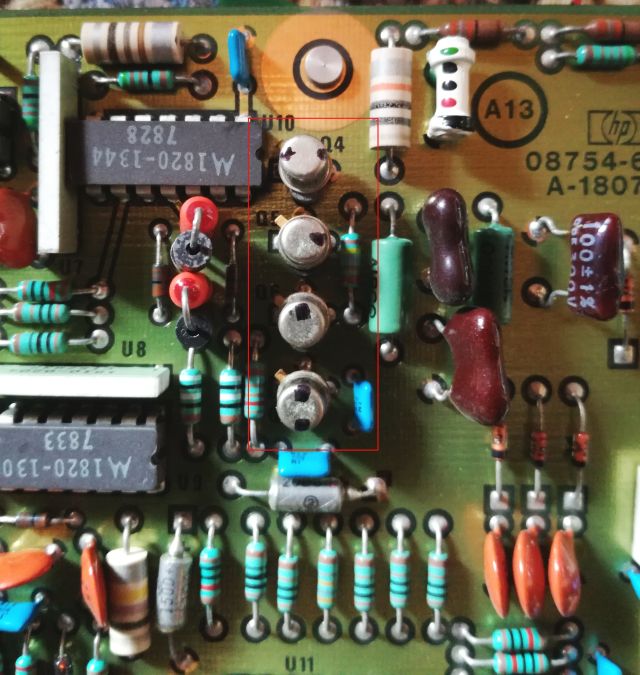

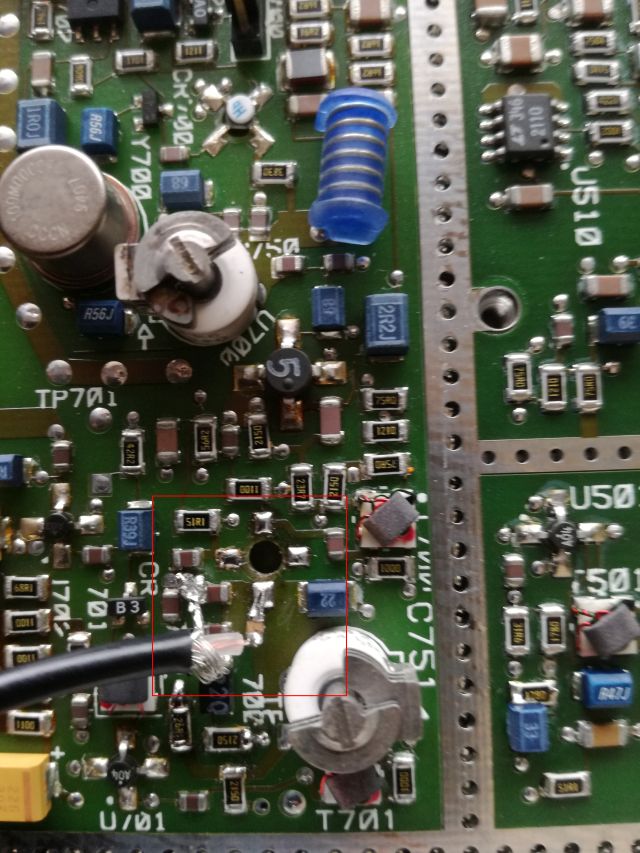

Finally managed to get all the sphere properly aligned. If you don’t know how it works, never turn the YIG spheres! These need to be aligned for thermal stability effects, not only amplitude – something which you may have trouble doing at home.

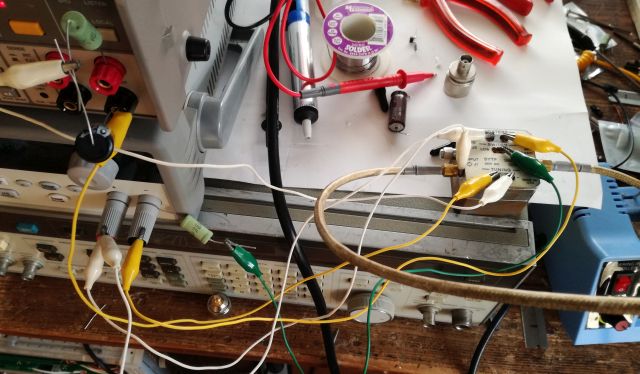

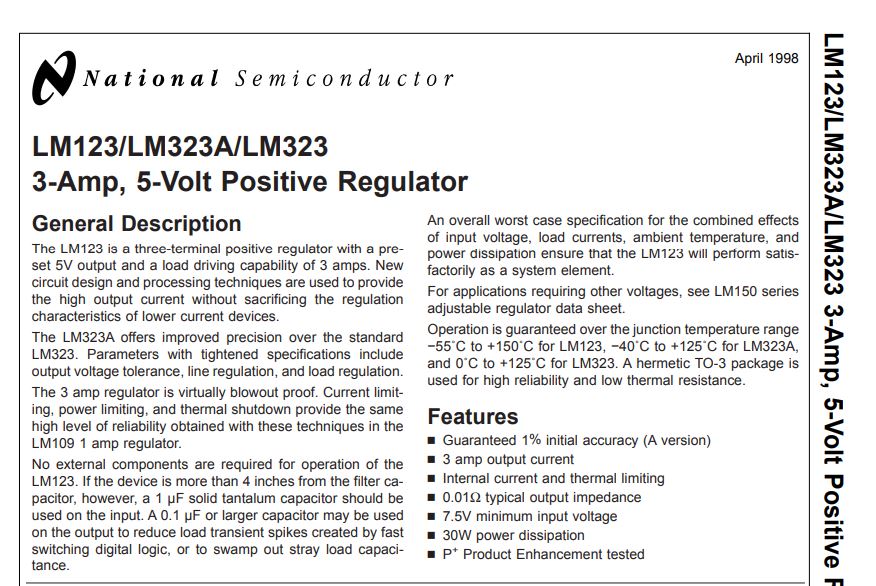

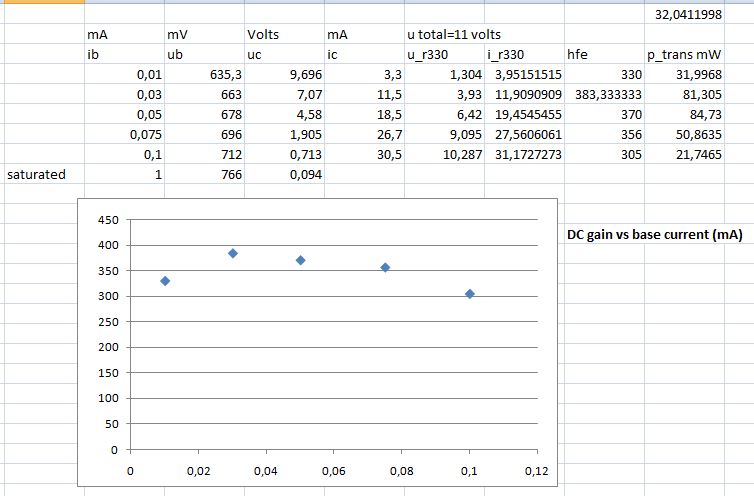

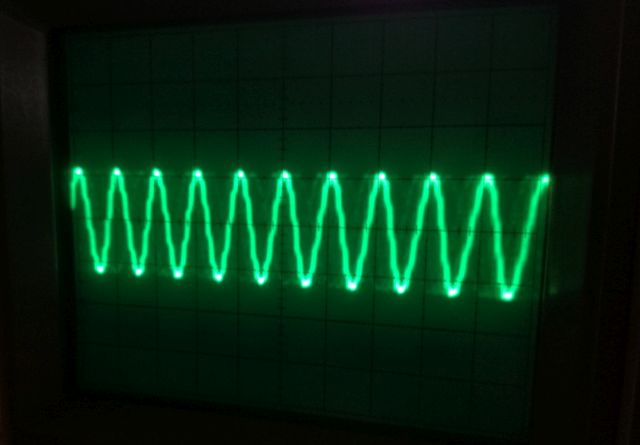

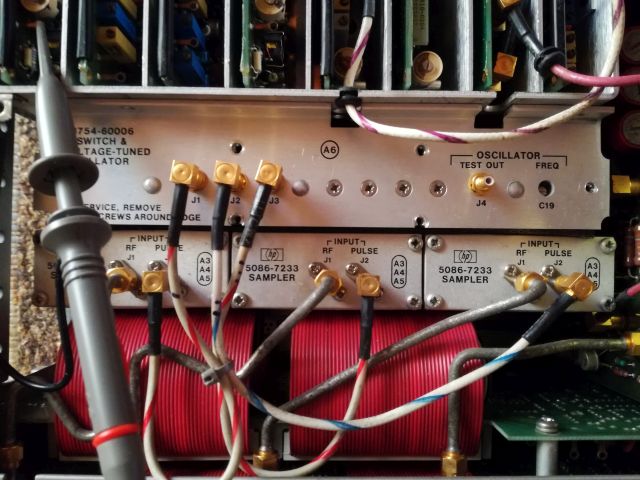

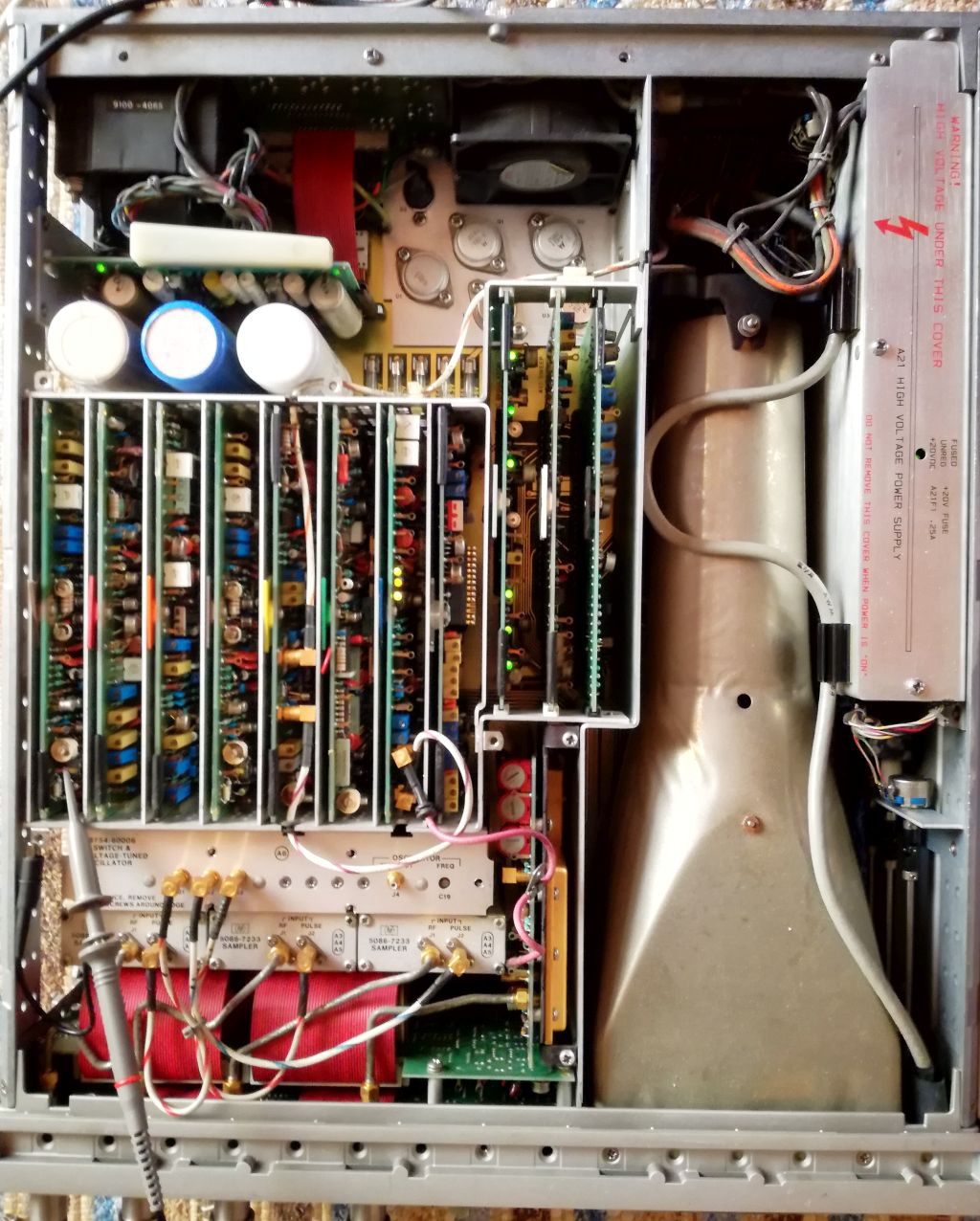

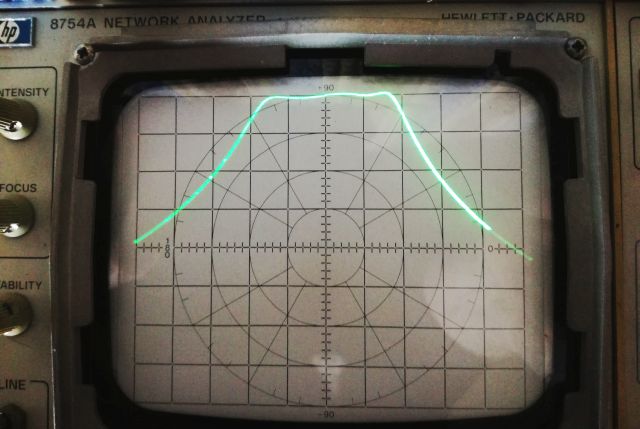

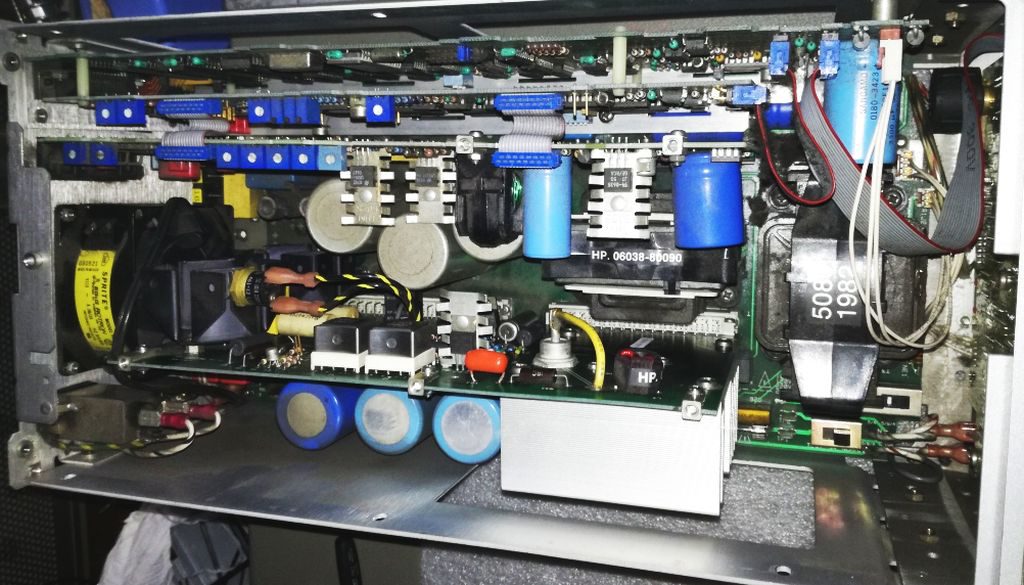

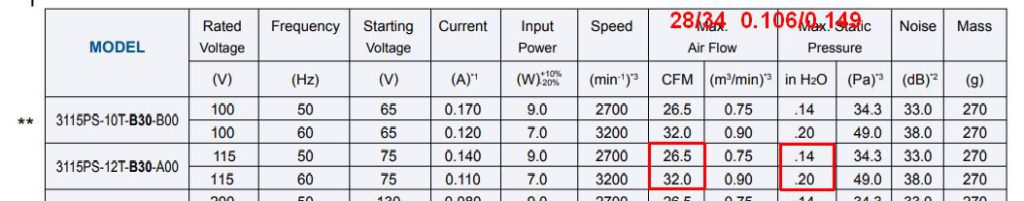

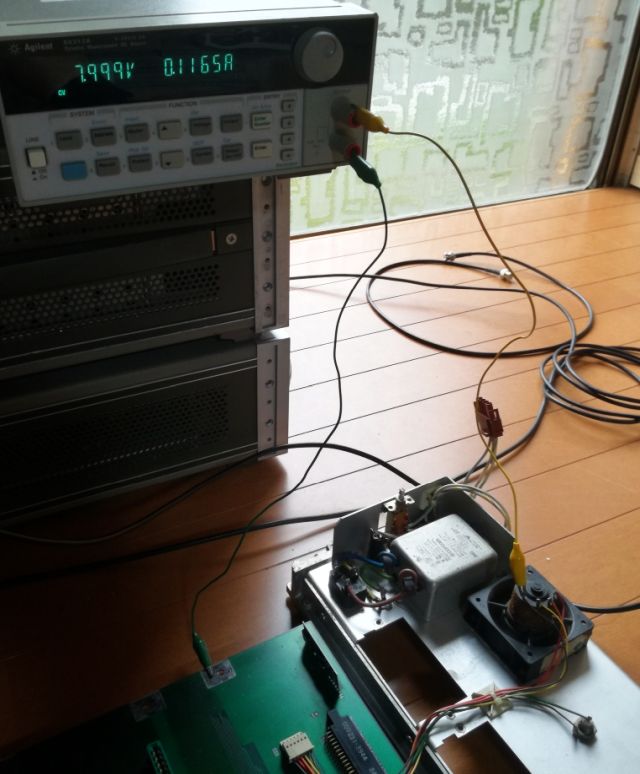

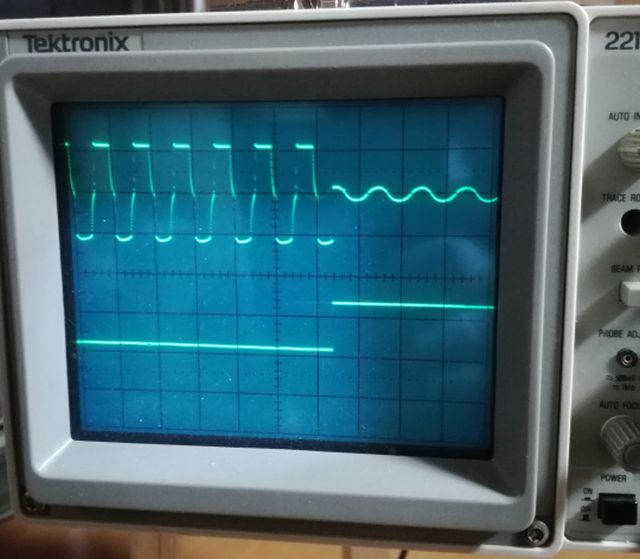

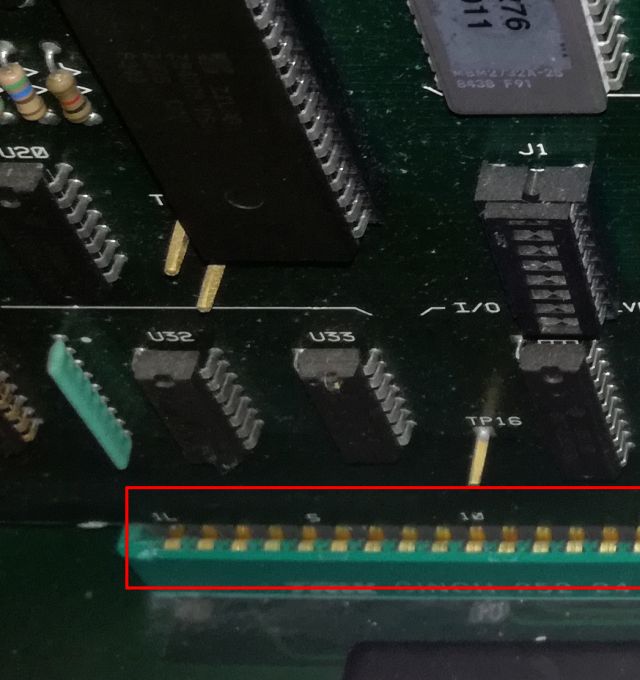

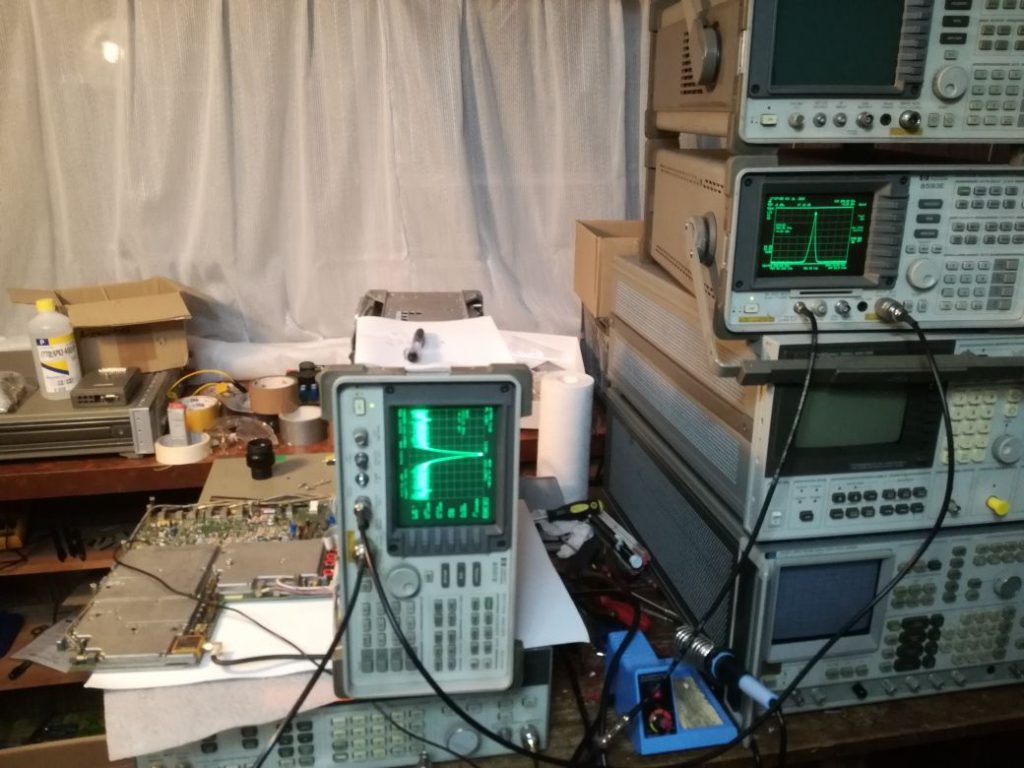

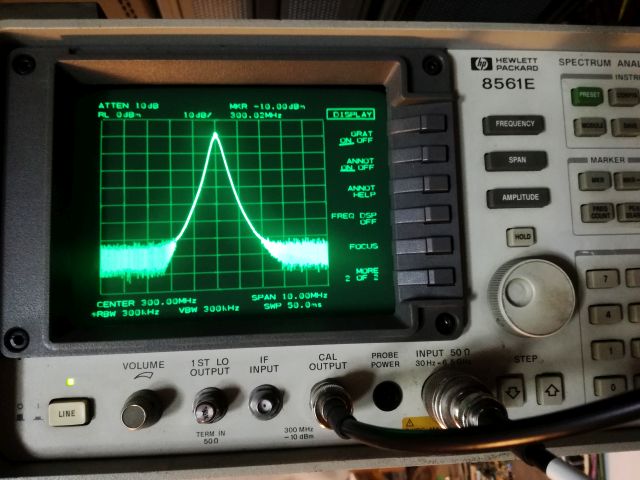

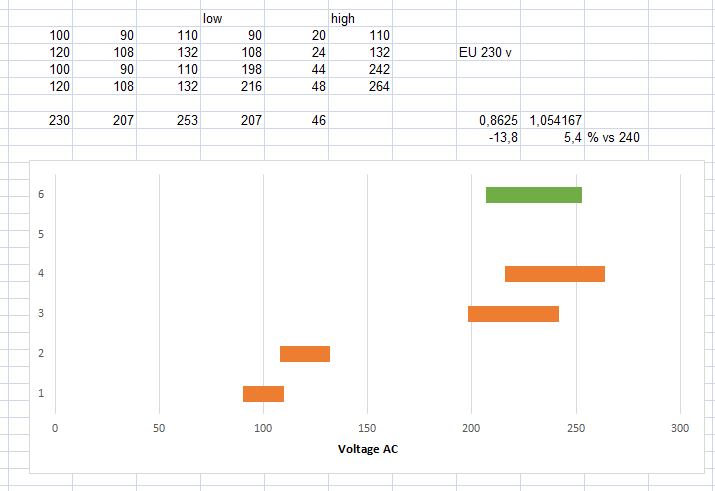

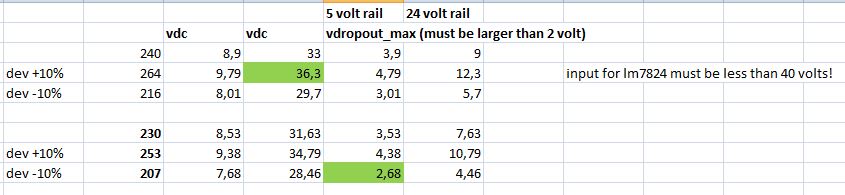

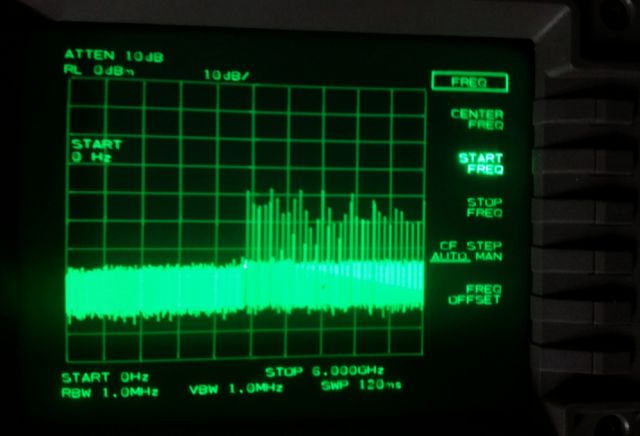

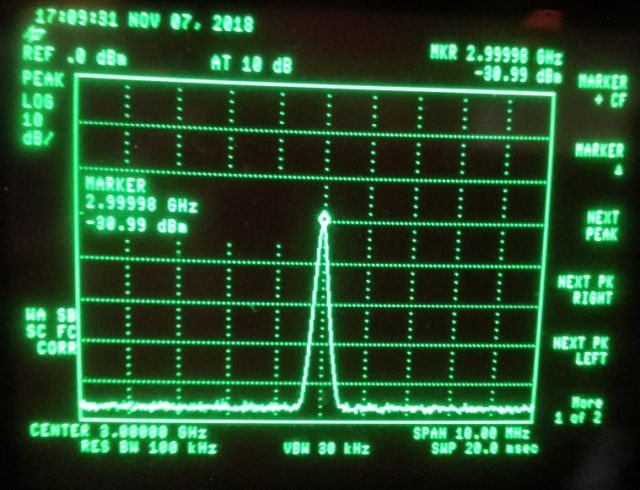

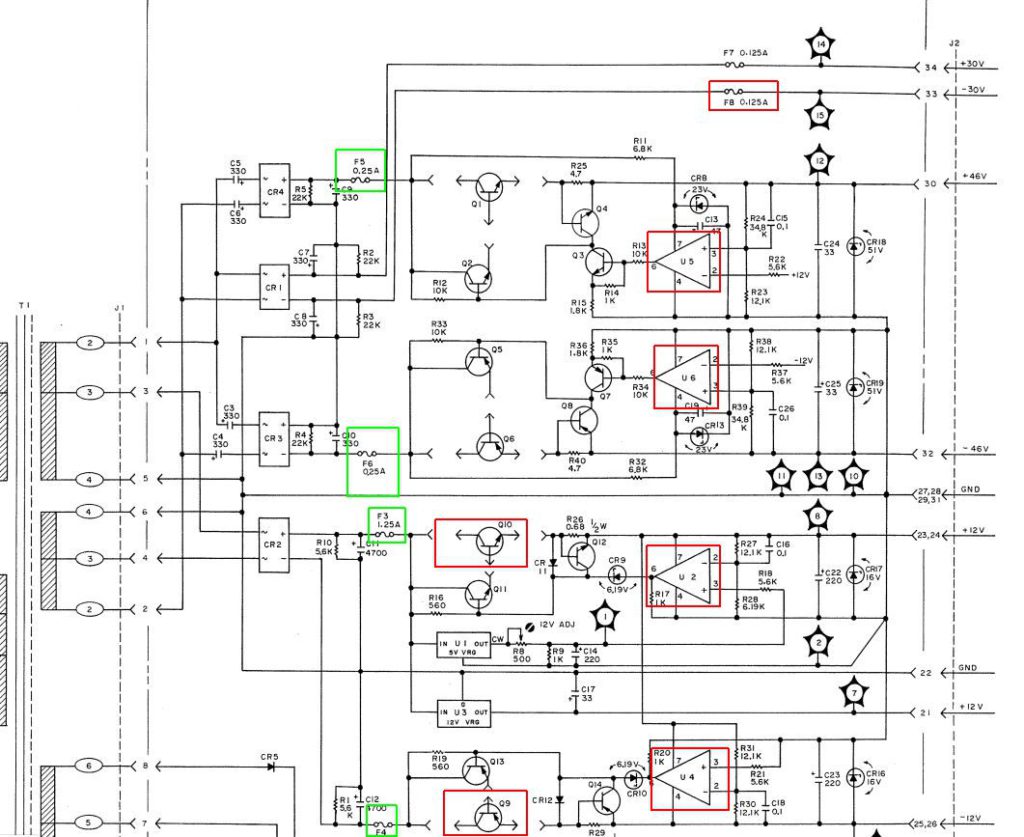

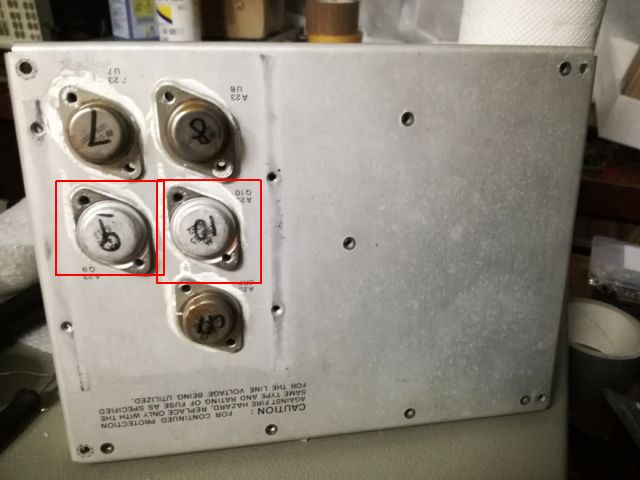

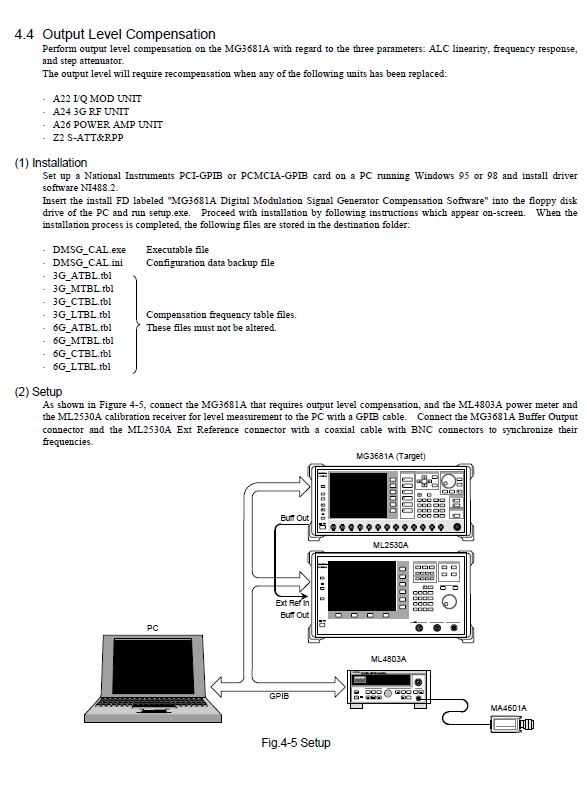

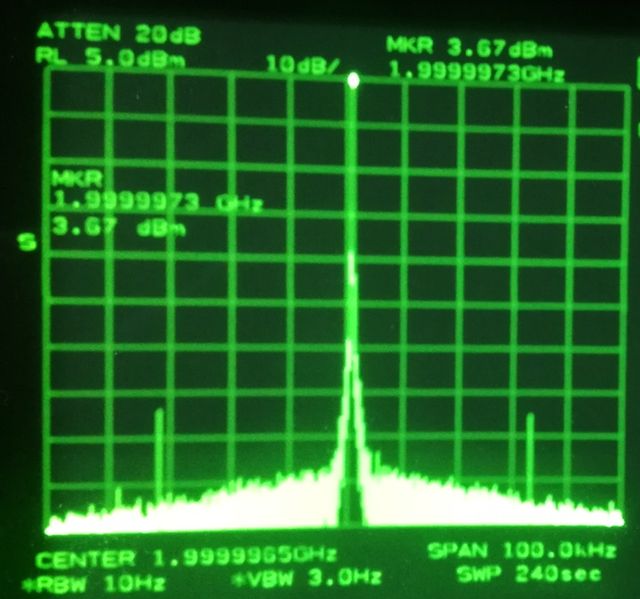

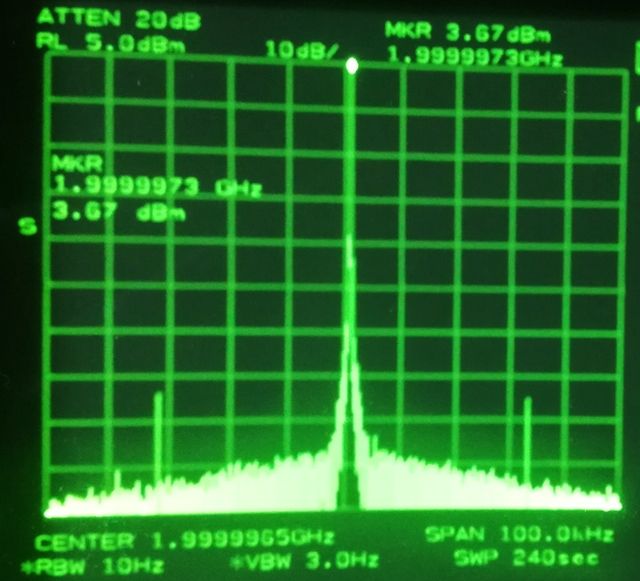

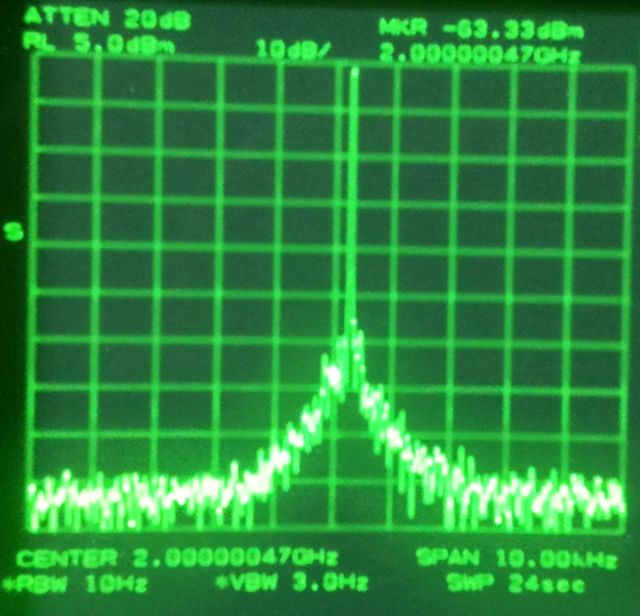

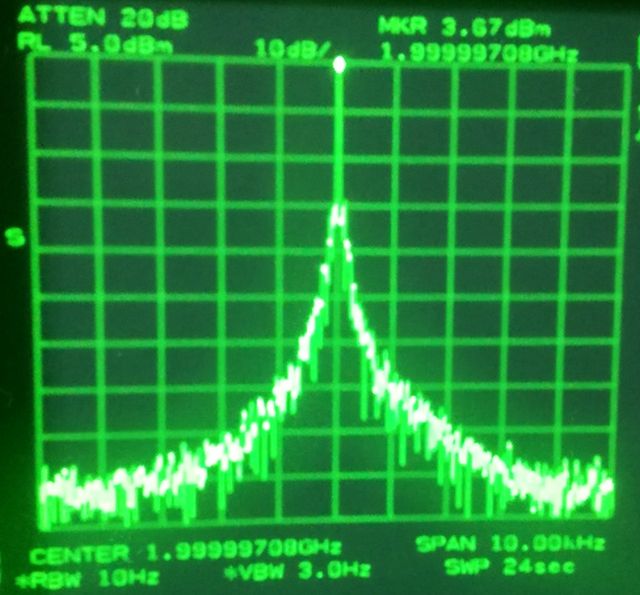

After all the alignment, a quick test setup, with a current source for the main coil, and another supply for the heater and switch connection. Note that the current source is set in parallel with a capacitor (22 uF) to allow for stable regulation with the strongly inductive load.

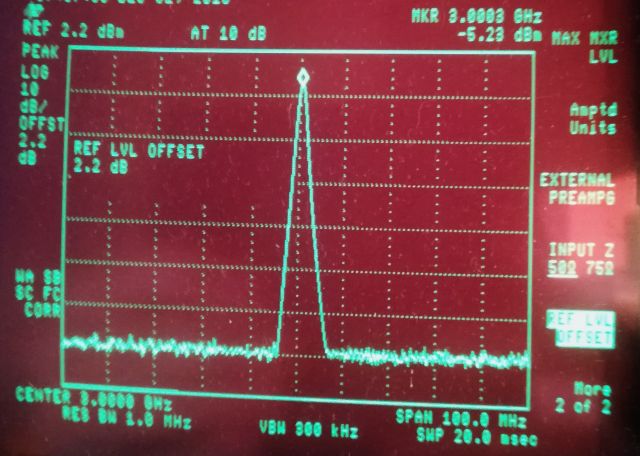

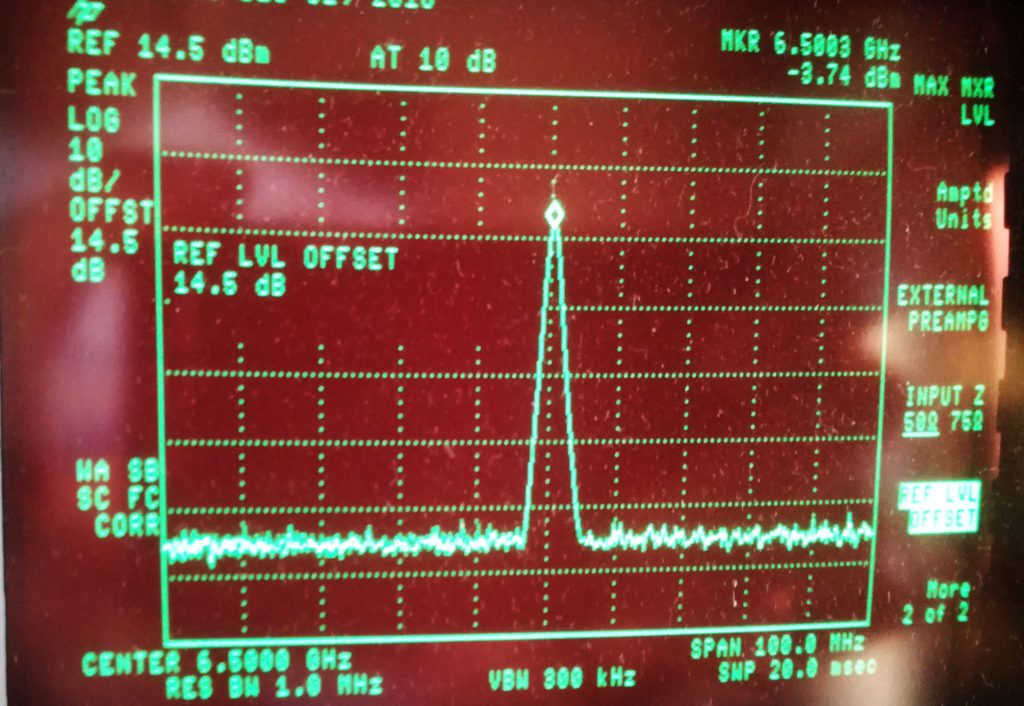

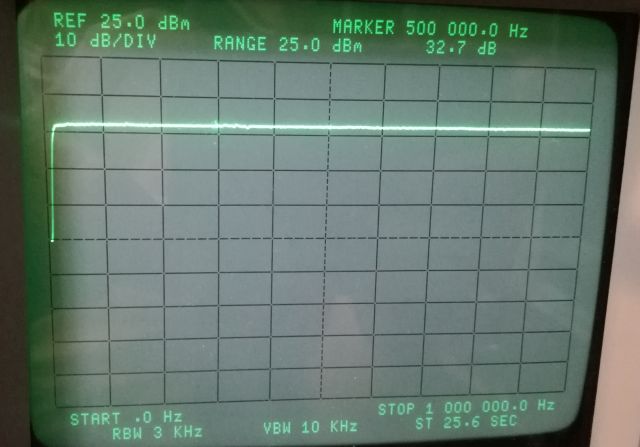

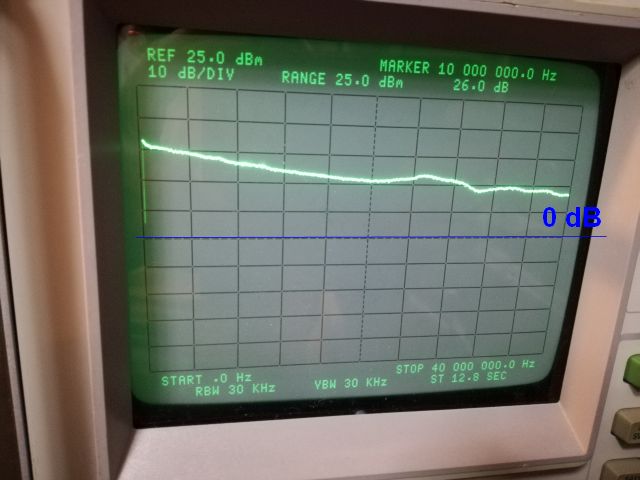

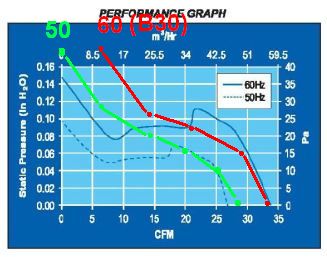

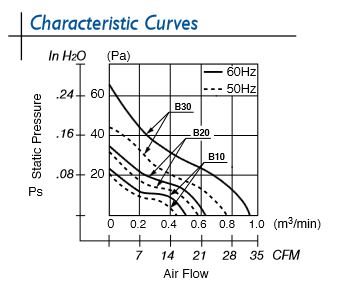

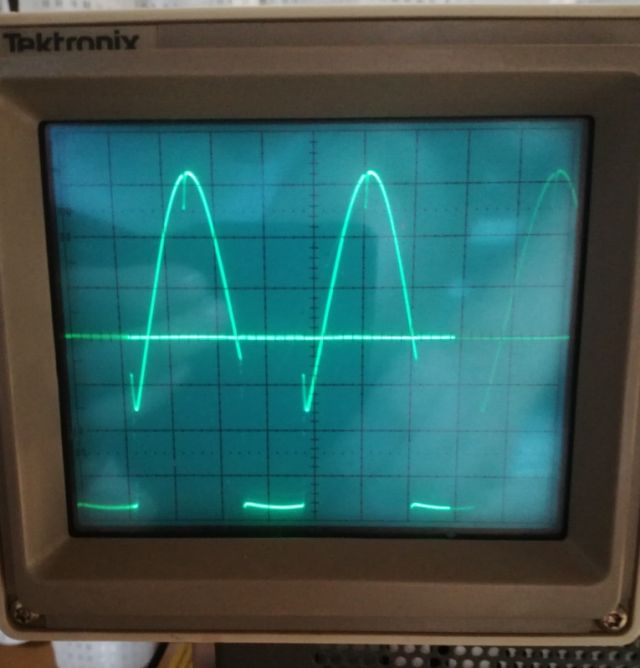

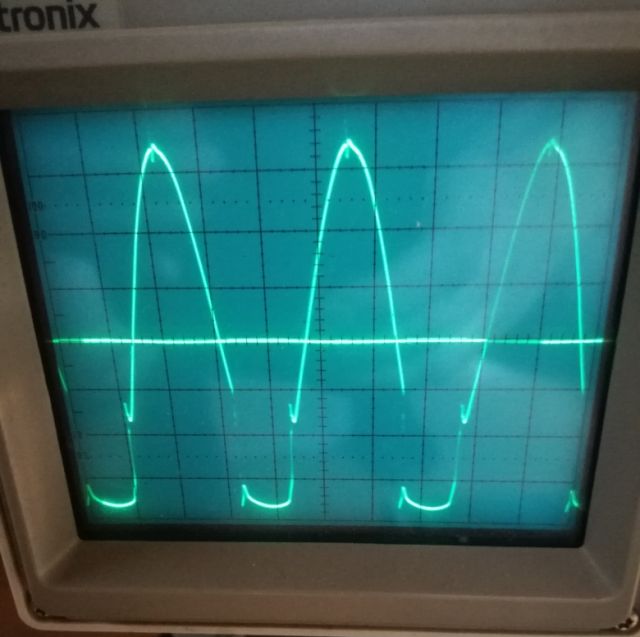

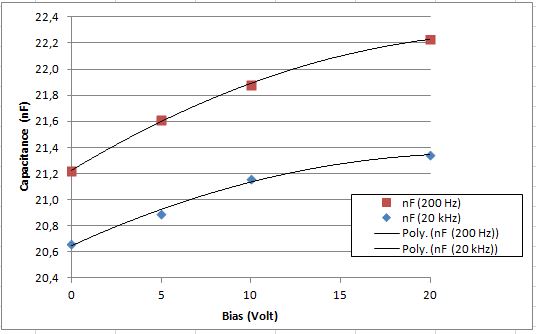

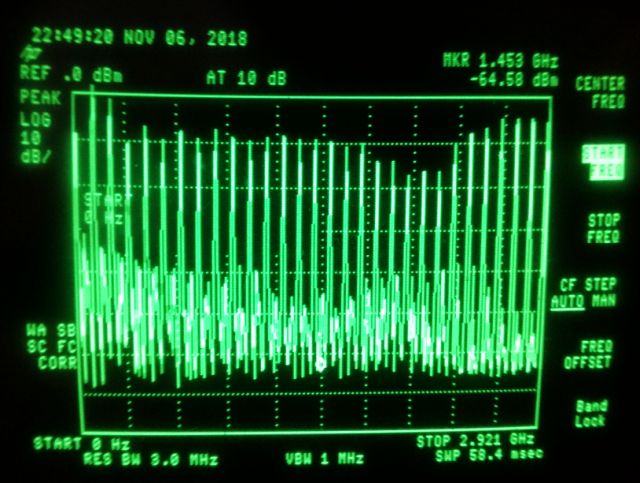

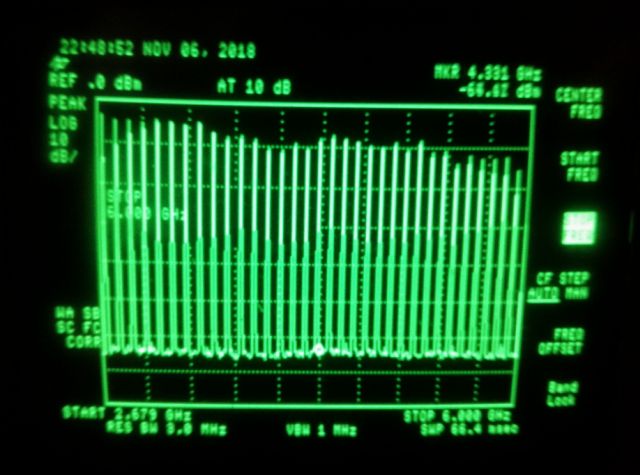

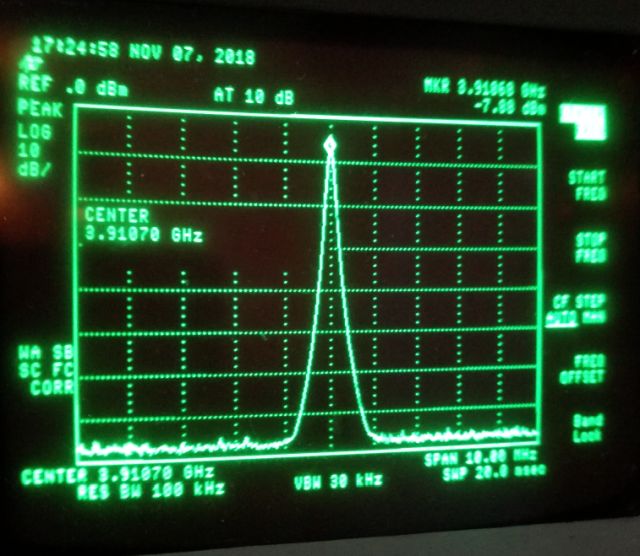

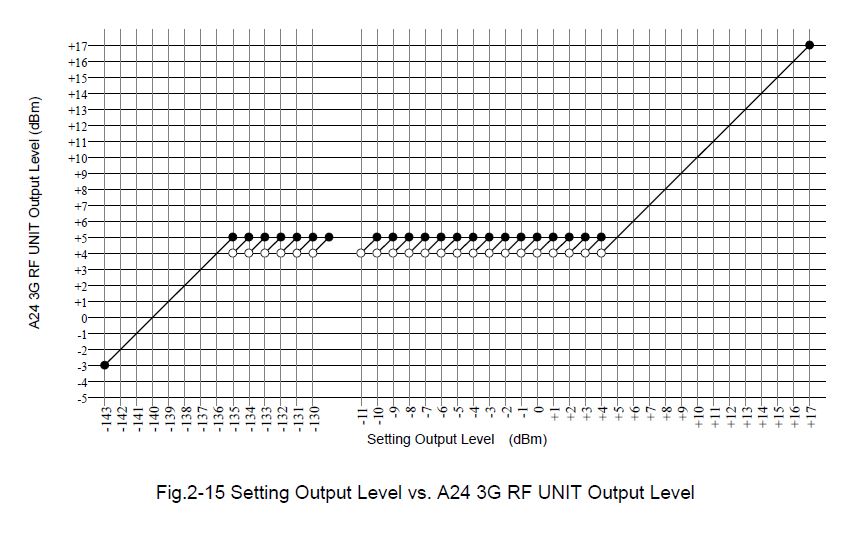

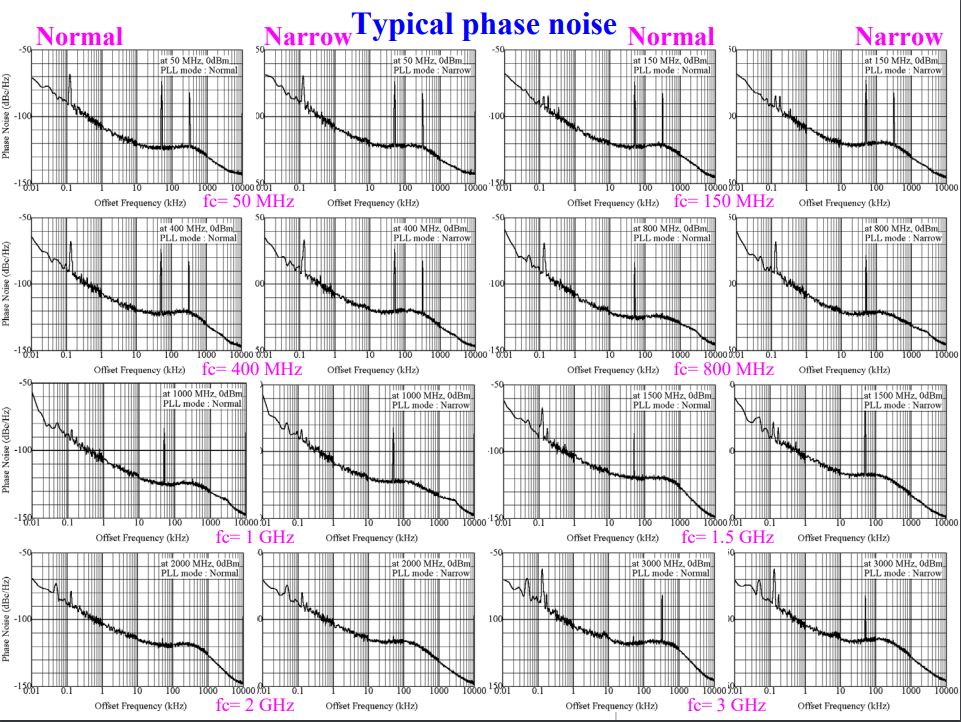

The insertion loss test – done by checking at several frequencies, using the lines of a good comb generator.

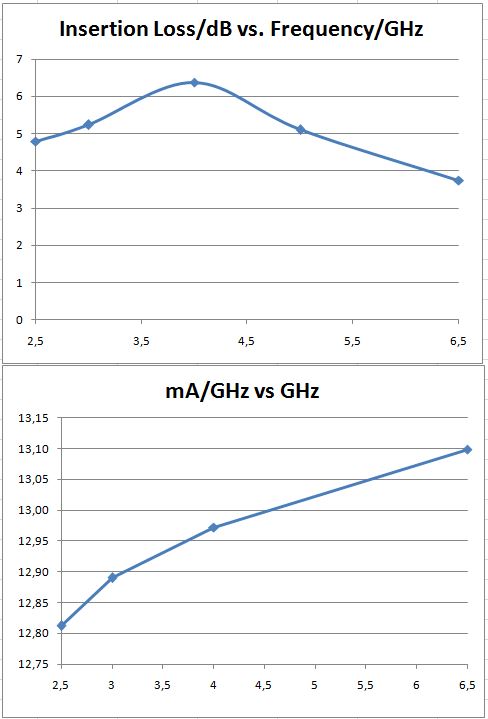

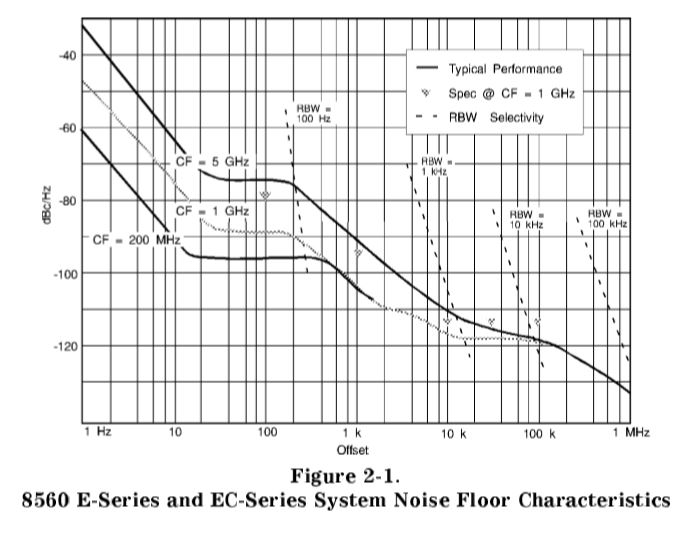

The insertion loss, in my simple setup, it is about 4-6 dB for a 3 stage filter, not bad. I don’t know the original performance spec, but it is definitely in the typical range of such filters, and good enough for a spectrum analyzer in any case (in the worst case, we will loose 1-2 dB of sensitivity). Maybe I will eventually find a new filter at a reasonable price, to check it – it could also have moved spheres.

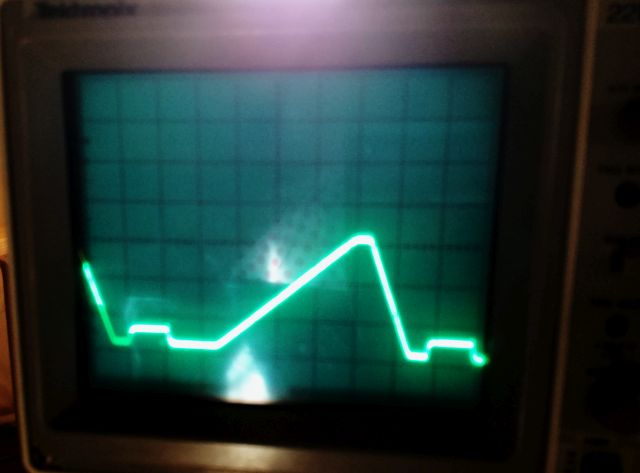

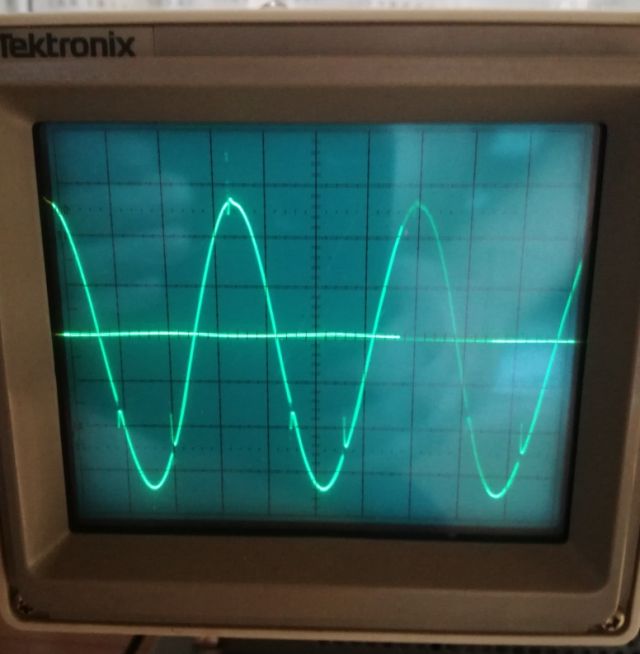

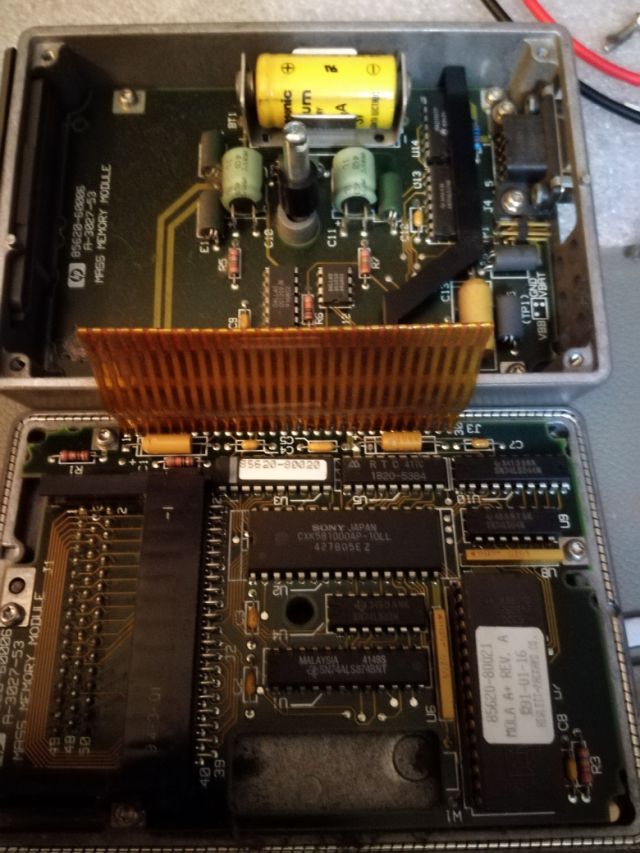

The tuning current is very linear, I don’t expect any issues with using this part in the analyzer (the tuning characteristics can be programmed and stored in the EEPROM of the analyzer, to control its DAC appropriately, also, we will need to recalibrate the flatness).