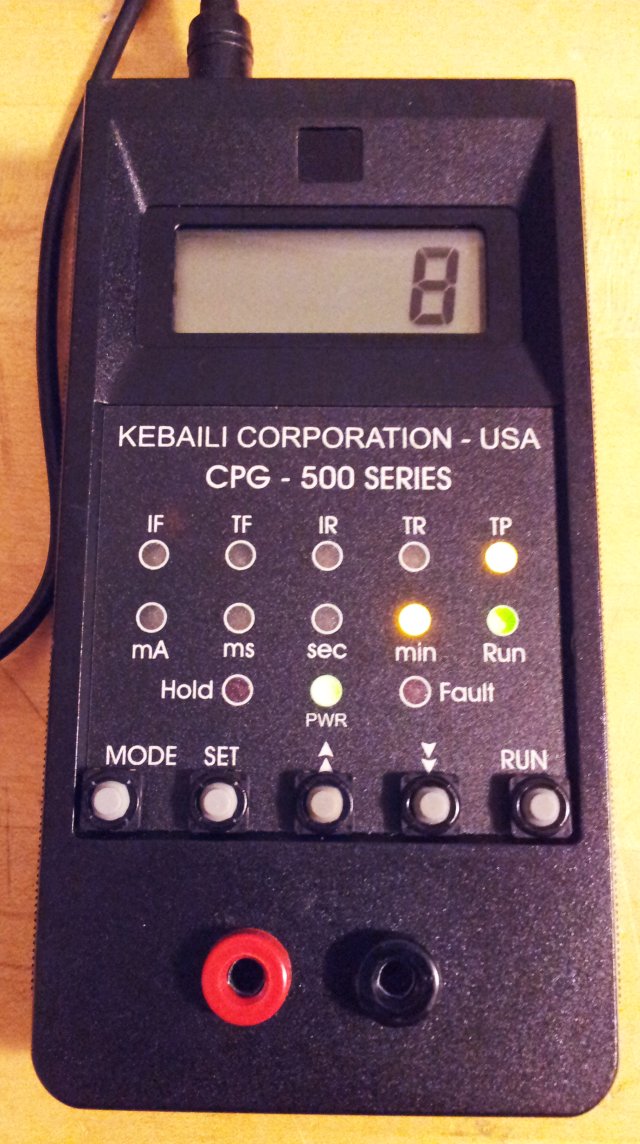

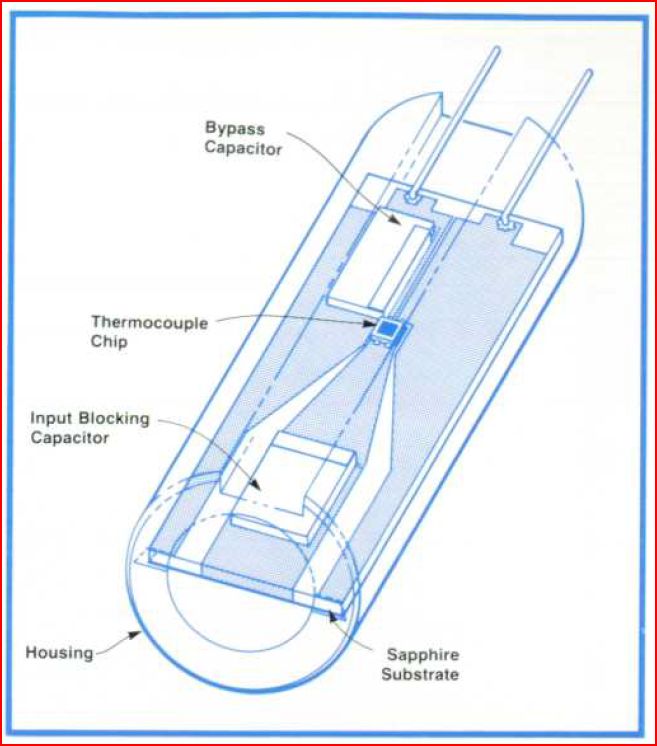

A rather rare guest in the workshop, a specialized power supply, for reverse pulse plating. Most of these are huge boxes used in the plating industry, with current rated in 10s of Amps, but this device is made for the semiconductor field, for depositing metal on silicon, for MEMS (micro-electro-mechanical) devices, etc. It’s a rather lightweight device, in a handheld case, powered by an external DC power supply.

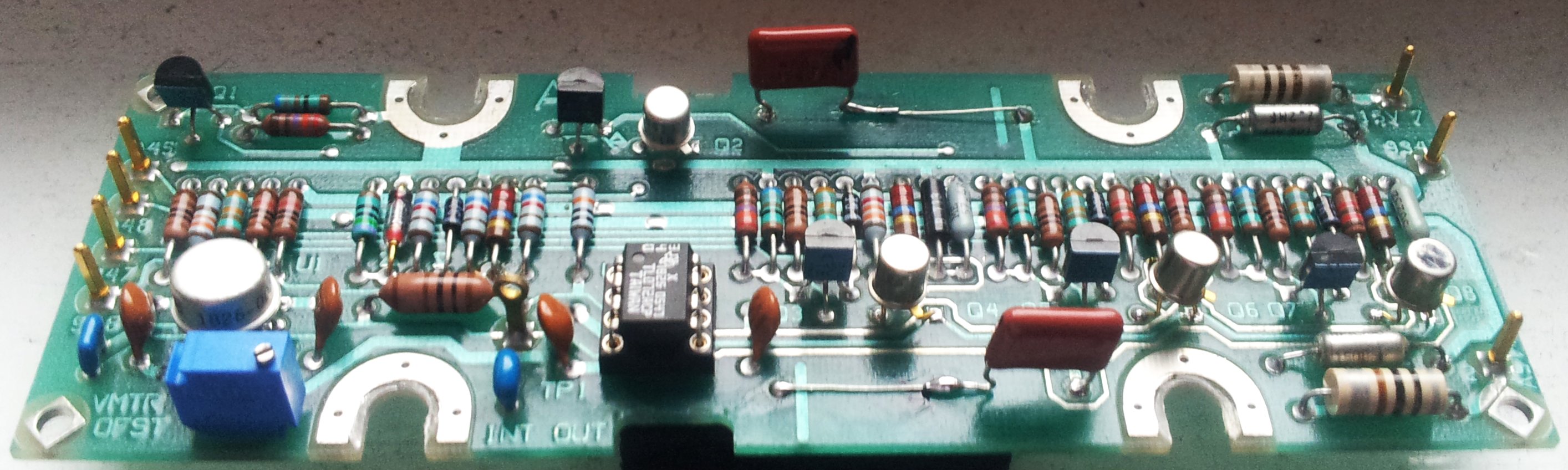

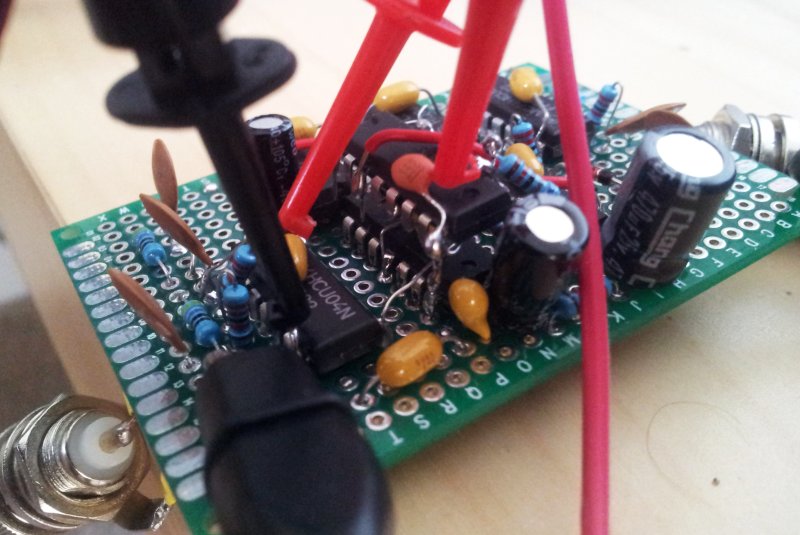

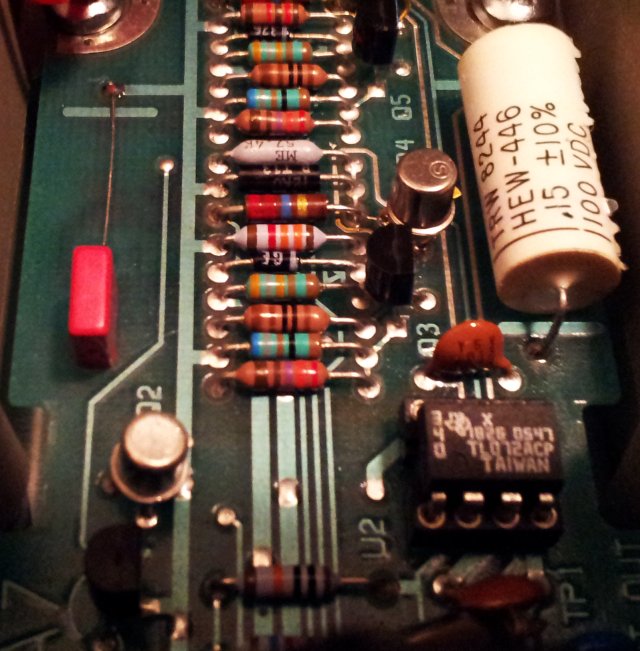

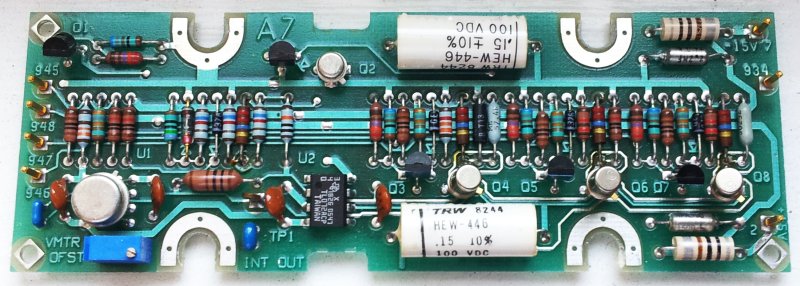

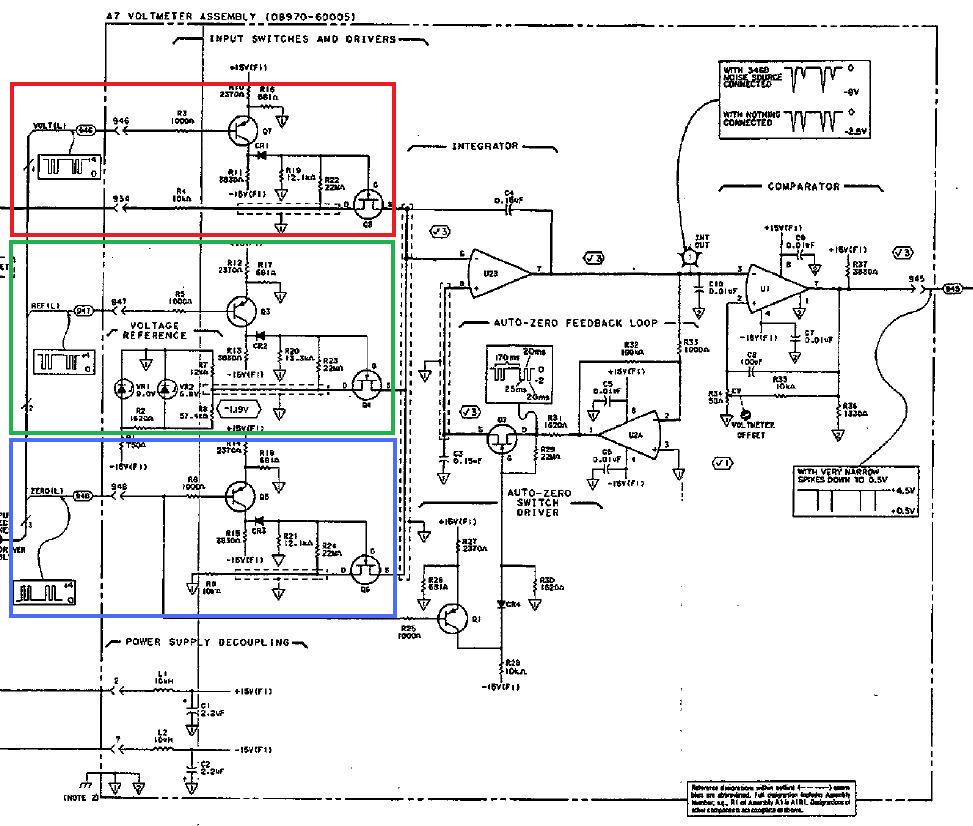

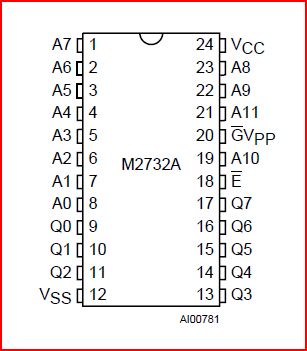

The internals show a construction which is more like a prototype than a fully engineered device. Epoxy glue is used to hold in the buttons, and Capton tape at various places. Well, some prototypes last forever, and it is certainly build to a good standard. The folks building it were very concerned about their design it seems, and removed all the marking from the parts used! Keep in mind, this is just a pulse current supply – why all the effort, and why make it so difficult to repair! Even more striking is the fact that the company manufacturing these is now out of business, with no information available whatsover, and no service provided (at least, I was able to obtain the user manual from the owner of the device). Please, leave the markings on the circuits, they are there for good reason – to let others fix the devices, when your greed and protective nature has ruined your business.

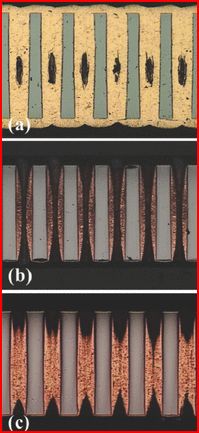

A few words about reverse pulse plating. You all know the through-hole plated circuits boards, plated vias, etc. These are made by electrochemically depositing copper, a method which Faraday and others invented long ago, but only in recent decades refinements were made to the current profiles to get nicely through-plated (and also filled) holes. Being able to deposit copper in cavities of any shape, etched into other materials, opens up a tremendous number of applications (e.g., complicated patters can be etched into silicon using the well-established methods of the semiconductor industry, then filled with copped – after removal of the silicon by selective etching, the small copper parts remain, resembling all the detail etched into the silicon).

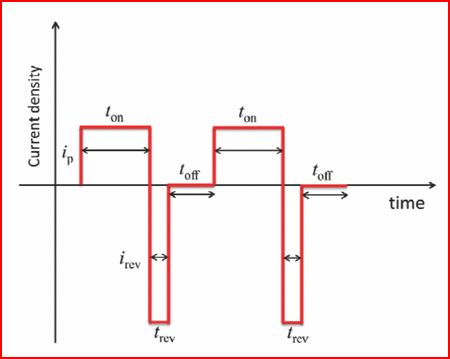

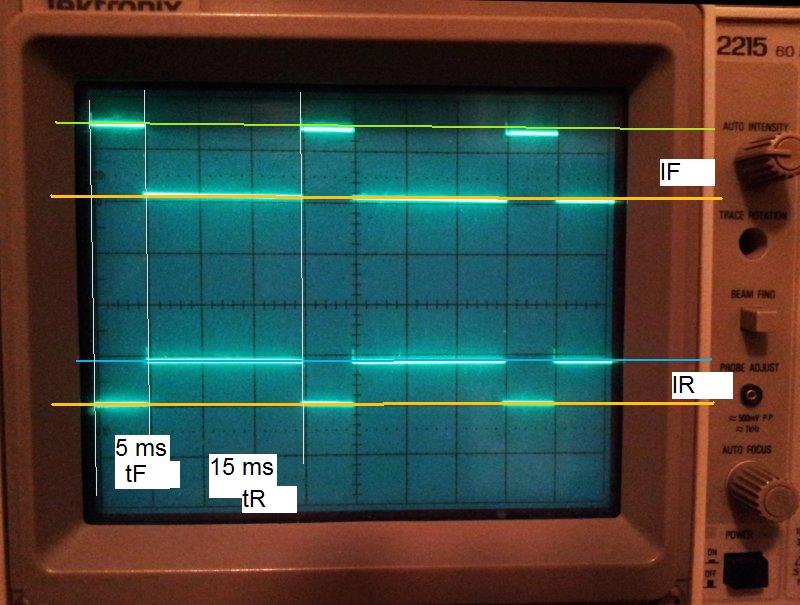

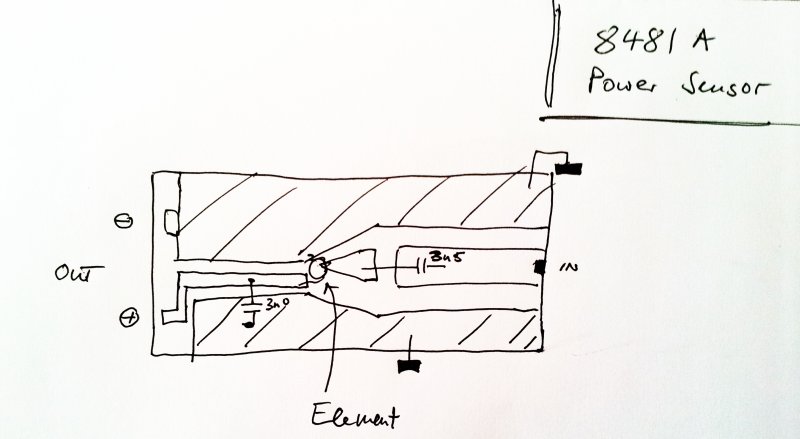

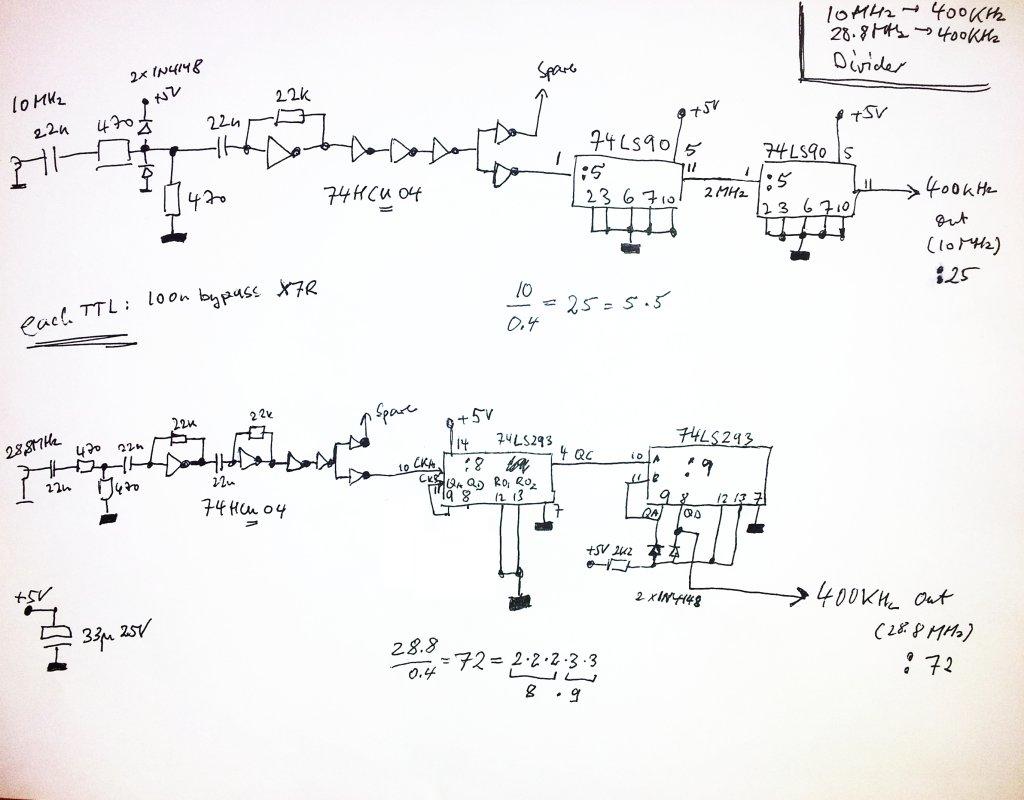

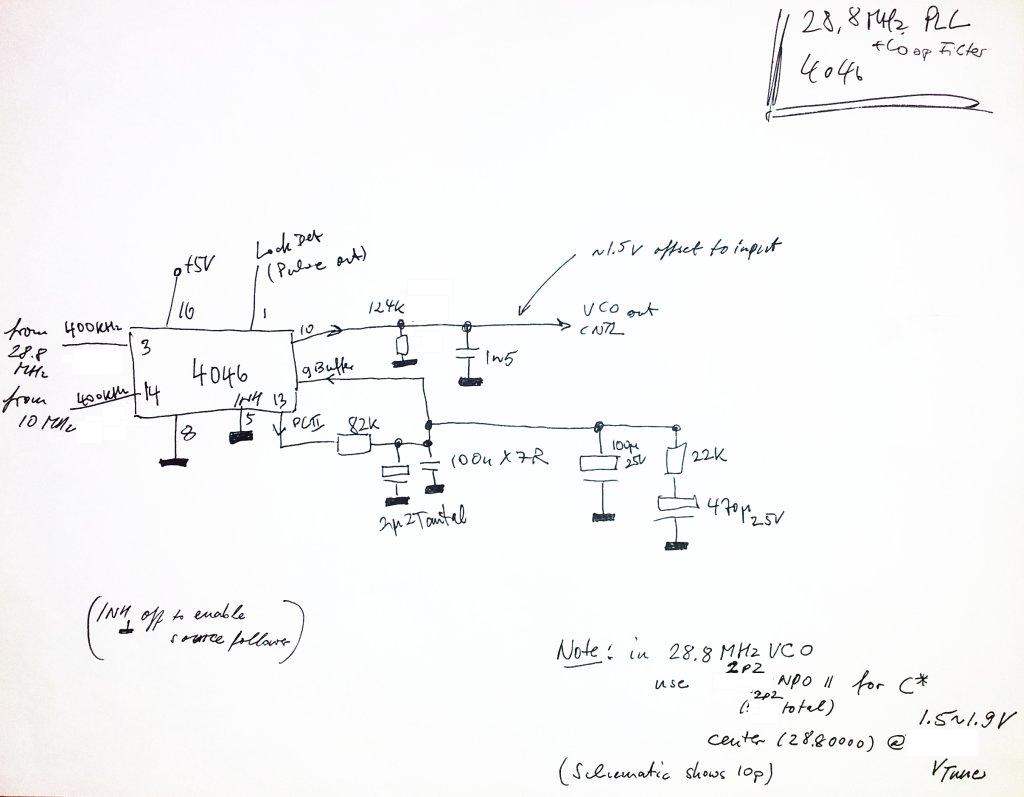

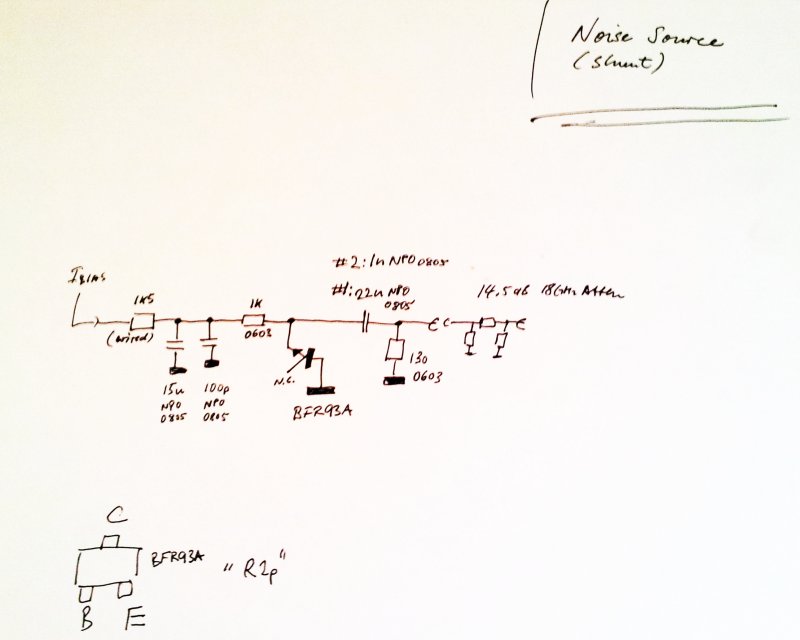

Here, the general pulse sequence: forward current pulse, reverse current pulse, idle time (no current).

A plating example (not from my lab), (a) shows a not properly plated through-hole (cavity in center) resulting from conventional plating; (b) and (c) are pulse plated – one can see how nicely the copper is growing, even in the center. Needless to say, all can be adjusted by selecting the right mix of chemicals, and by optimizing the current levels and pulse duration for the desired results (filled hole, filled cavity, wall-plated hole, and so on). Typically pulse times are milliseconds. But can be 10s or 100s of milliseconds, in cases.

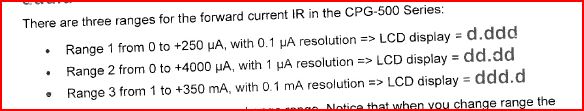

The CPG-500 has 3 current ranges, quite a flexible device, to cover applications from micrometers to square centimeters…. resolution is about 1:4000, about 12 effective bit.

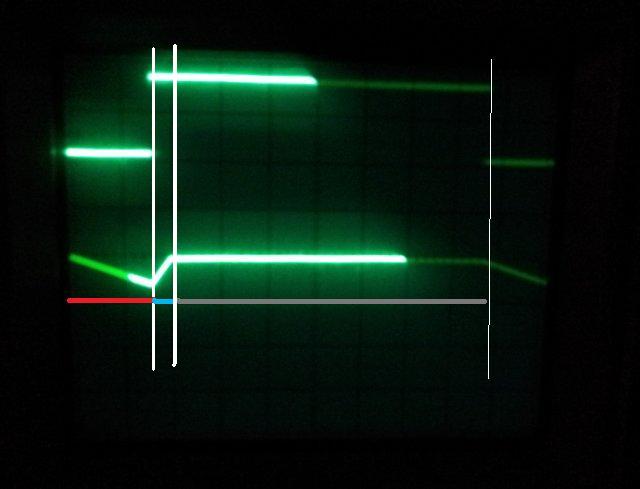

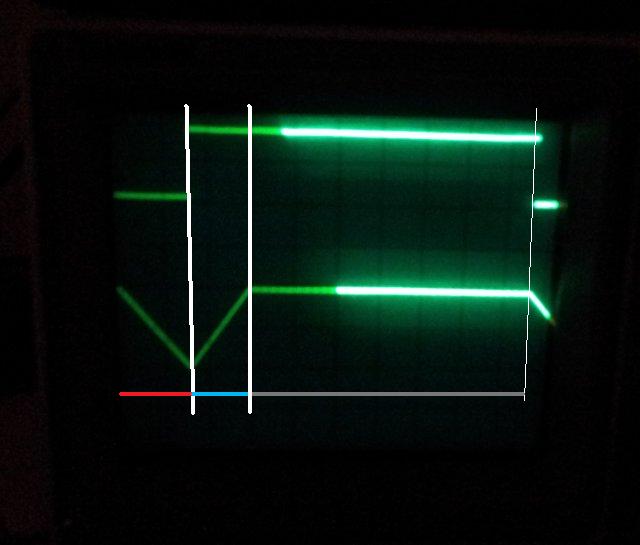

After some repair, no spectacular enought to write about, these are the output signals. Pretty clear how it works – lower trace is forward current, upper trace reverse current – during operation, the current sources is switched from one output to the other and back, grounding one of the outputs at a time. When switched off/when plating is finished, both outputs are switched off/high impedance, with no current flowing. Orange lines are 0 V ground potential of the power supply.

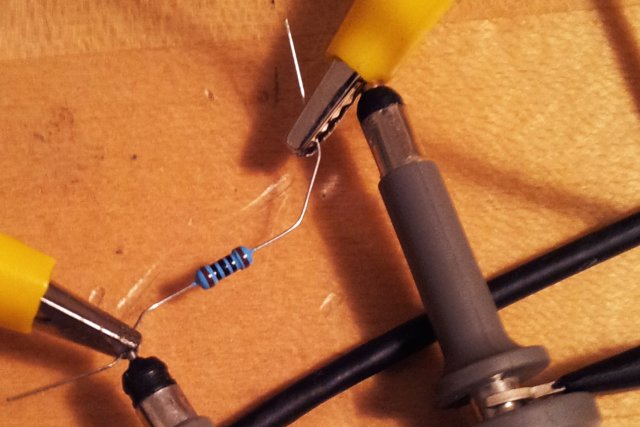

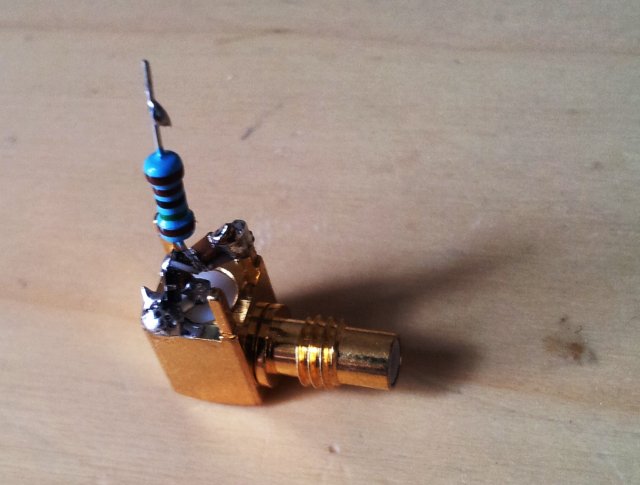

Because of the way this bipolar operation is realized (by unipolar switching of current), probing the current requires a few tricks. A 100 Ohms resistor inserted in the current path (in series with an amp meter), and two oscilloscope probes.

The scope is then used in ‘add inverse’ mode to subtract the two signals, resulting in the display of the actual forward and reverse currents, as one trace.

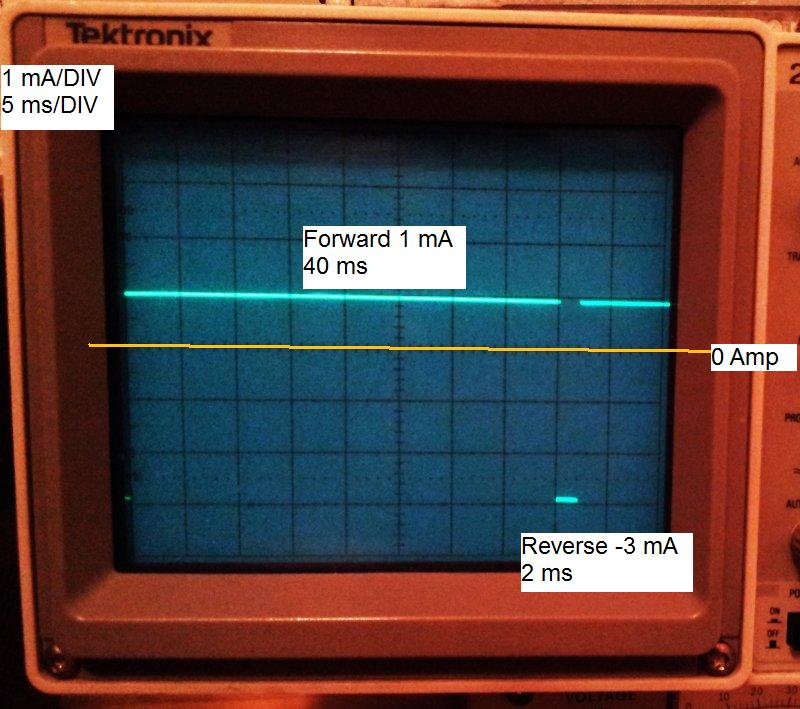

This is a quite typical waveform, the reverse current is 1.5-3x the forward current, at about 2-10% of the duty cycle. This example as 1 mA forward current, 3 mA reverse current, 40 ms forward, 2 ms reverse pulse (i.e., current ratio is 3, and time ratio is 20). This results in an average current of (40*1-2*3)/42=0.8095 mA. An, not really surprisingly, this is what the amp meter shows.

Call it fixed!